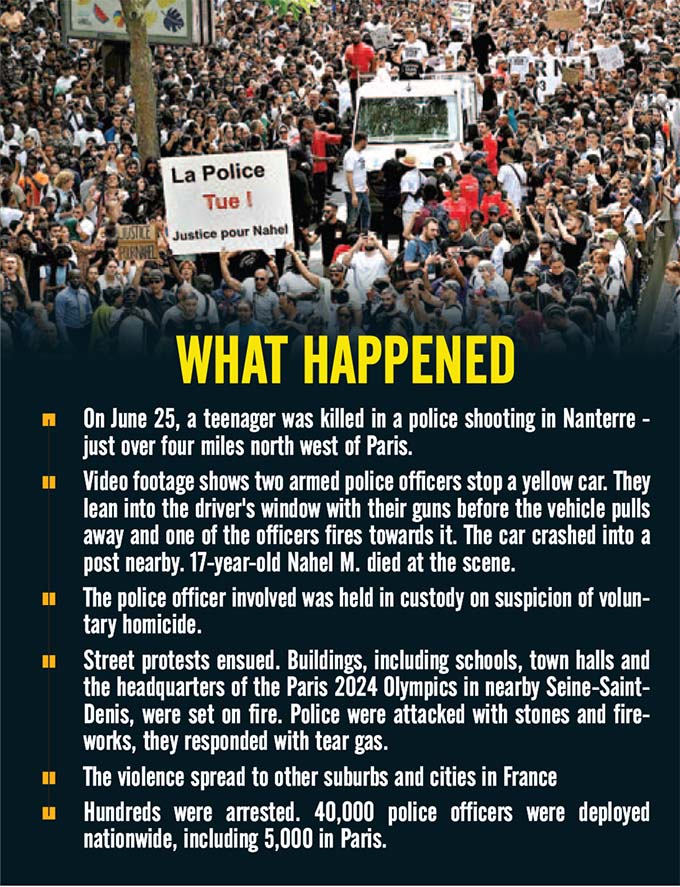

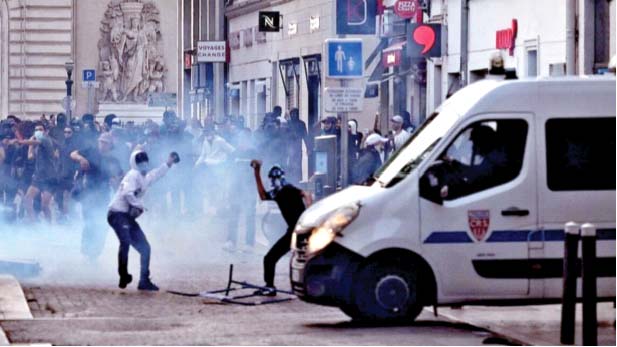

France celebrates Bastille Day on July 14. It is celebrated in commemoration of the storming of Bastille by the revolutionary forces in French Revolution. As France is gearing up to celebrate the day with grandeur, an incident on June 30 caused a huge unrest in the French republic, shaking the foundation of the very principles it is founded on. On June 27, 2023, a 17-year-old Nahel Merzouk was killed when police fired at him as he was driving a car. What followed was arson and loot, with armed gangs of teenage protestors challenging the French law enforcement agencies, attacking symbols of state such as town halls, schools, police stations and other buildings. Nahel’s name has become synonymous with George Floyd of Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement except that Nahel happened to be an Arab Muslim of Algerian-origin born in France.

Police Brutality or Preemptive Action

Police brutality is a significant issue reported and documented in several countries, including France. Instances of police misconduct and excessive use of force have raised concerns among human rights organisations and citizens alike. While not all police officers engage in such behaviour, the actions of a few individuals can have a profound impact on public trust and confidence in law enforcement.

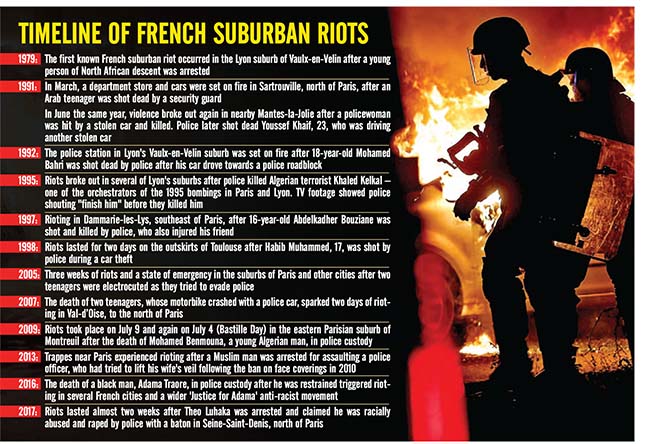

In France, cases of alleged police brutality have sparked public outrage and led to protests demanding accountability and justice for a long time. One notable incident occurred in 2016 when a young black man named Adama Traoré died while in police custody. His death and the subsequent handling of the case raised questions about the use of force by the police and the treatment of marginalised communities. Similarly, the “Yellow Vest” movement, which began in late 2018, also witnessed incidents of alleged police violence. The movement initially started as a protest against hike in fuel tax but soon evolved into a broader expression of frustration with social inequality and economic grievances. During some of these protests, there were reports and video evidence of police officers using excessive force, such as tear gas, rubber bullets, and batons on protesters.

“Is it a permanent return to calm? I will be cautious, but the peak that we’ve seen in previous days has passed” -Emmanuel Macron French President

These incidents, along with others, have resulted in public debates about police practices and the importance of ensuring accountability. The French Government has acknowledged the issue and initiated reforms to address concerns about police violence. In June 2020, a ban on the use of chokeholds by police officers during arrests was implemented, although critics argue that more comprehensive changes are needed.

Another factor that gives impetus to police brutality in France is Islamist extremism. It gained prominence with a series of terrorist attacks that occurred in France over the last three decades, notorious of them being the Charlie Hebdo attack in 2015, the Nice attack in 2016, and the Paris attacks in 2015. These incidents led to heightened public awareness and concern about the potential risks posed by radicalised individuals from Islamic extremism, keeping the law enforcement agencies of France on tenterhooks.

Every person in France is required to submit to an identity check by the police. Foreigners are required to always carry proof of identification. Only adults over 18 years of age can drive a vehicle with a legitimate driver license. The driver of a vehicle is obliged to produce his driver’s license on demand by the police. Failure to do so attracts penalty in the form of fine and felony.

In the very recent past, Islamists used vehicles to carryout terrorist attacks in France. Such experiences plunged law enforcement agencies to confusion regarding the action plan or a policy to tackle incidents that involve terrorists ramming their vehicle into public with an intention of committing homicide. Since 2017, a law allowed police to use firearms in case of non-compliance during traffic stops, with the result that fatal shootings by officers have shot up, with 2022 witnessing a record 13 such shootings.

It is hard to get statistics about the traffic violations, crimes that involve a particular community in France as it is officially forbidden by the Constitution to create data based on ethnicity, religion and color which is where the problem lies.

Colour Blind State

Everything is absolute in France, be it Freedom of Expression or political egalitarianism. France is a “colour-blind” state where laws, Government policies, research and statistics that are based on race and ethnicity are prohibited. Race is such a taboo term that a 1978 law specifically banned the collection and computerised storage of race-based data without the express consent of the interviewees or a waiver by a state committee. France, therefore, collects no census or other data on the race (or ethnicity) of its citizens.

The non-recognition of race and ethnicity make it difficult to assess racism and to identify indirect and institutional racism in France. The only officially recognised distinction is between a French citizen and a foreigner. This means that it targets virtually no policies that address any racial or ethnic groups. Instead, it uses geographic or class criteria to address issues of social inequalities.

It has, however, developed an extensive anti-racist policy repertoire since the early 1970s. To counter problems of ethnic disadvantage, they have constructed policies aimed at geographical areas or at social classes that disproportionately contain large number of minorities. The Educational Priority Zones initiative, for example, funnels supplemental money to disadvantaged school districts, many of which contain large numbers of immigrant ethnic minorities. However, politicians and policymakers have insisted that the goals of such policies are to better the lives of localities or of all people in need and have avoided highlighting the racial and ethnic implications of their initiatives.

“France collects no census or other data on the race (or ethnicity) of its citizens. A 1978 law banned the collection of race-based data without the express consent of the interviewees

The law promulgated in 1972 is a cornerstone of how France views the subject of racism. The law made specific reference to race and ethnicity, outlaws’ discrimination in employment and provisions that allow the state to ban groups that seek to promote racism. It institutionalised the legal role of non-governmental anti-racist associations as partners in fighting racism. It was an anti-discrimination law and could not be invoked in, for example, a racially motivated murder. It is possible that a lack of emphasis on race in French criminal law contributed to police officials overlooking racist motives in many crimes which includes Nahel’s case. As a result, the state relies on the criminal law to prosecute such offences, because the penal code requires a higher burden of proof than the civil code.

After several attacks on synagogues and violent anti-migrant crimes, the French Communist Party proposed a new anti-racist law. The French Socialist Party lobbied for a new law to prohibit “negationism” and history “revisionism” in 1990, but the new law was also considered a limitation on the right to Freedom of Speech and Expression in France.

In 2000, France experienced an increase in violent anti-Semitic attacks against persons and property. These attacks were perpetrated by North-African Arab, youth who regarded themselves as oppressed.

The Charlie Hebdo attack in 2015 was also linked to an increase in anti-Muslim crimes and sentiment in France. The French Government introduced several measures to restore law and order. The first Intifada commenced in Dec 1987 and the second Intifada commenced in the latter half of 2000. Both were accompanied by attacks by North-African Arabs on Jews in France.

The French Human Rights Commission revealed that in 2002, 62 per cent of racist crimes were anti-Semitic in nature. In 2003, 72 per cent of racist crimes were anti-Semitic, and the Minister of the Interior and the Minister of Justice began advocating stricter law-and-order measures.

Within the context of France, a law was passed in 2001 that gave police the right to stop and search without reasonable grounds to believe that the person concerned had committed, or had attempted to commit, a crime. A new law was passed in 2003 that imposes harsher penalties for certain existing violent offences when they are motivated by the ethnicity, race, religion, or nationality of the victim. The law would also heighten policing in the cities and increase the surveillance of mosques and stop-and-search practices in Muslim-dominated areas.

To address resentment among immigrants, France has introduced several Government initiatives that indirectly recognise racial and ethnic differences. In addition, it has made efforts to recruit more youths of immigrant origins into the police force but that yielded no results. The French Constitution of October 4, 1958, was amended in 2014 to refer to the equality of all citizens before the law, without distinction as to “origin, gender or religion”. While it may sound altruistic and pragmatic on paper, but it did more harm than good. The French idea of assimilation was meant to turn all its former colonial subjects into one-dimensional Frenchmen, stripped of their alternative histories and the ideas and concepts about identity held by their ancestors, say sociologists and historians. Several writers have advocated for the greater recognition and collection of race and ethnicity in France to form future Government policies and laws.

Civilisational experiment gone wrong

After the end of World War II, throughout the economic miracle from 1950s to 1970s, France began recruiting migrant labourers from its other former colonies in North and West Africa. The Moroccan and Algerian communities in France are diverse, comprising individuals from different ethnic, cultural, and religious backgrounds. These migrants were housed in low-income housing, and a “threshold of tolerance” principle was applied to avoid the creation of ghettos. This led to the concentration of large of swaths of people belonging to one ethnicity and religion causing an isolation from rest of the French society. The successive generations made no effort to assimilate into the mainstream of French society. Many of immigrants of second and third generation complain that the French society looks down upon them.

Most youths of North-African Arab origin are French citizens, but most feel they were never fully accepted in France based on their religion, ethnicity, and poverty. As a result, most of the suburban parts of French cities are plagued by high levels of unemployment, overcrowded living conditions, a high school dropout rate and greater visibility of youth on the streets. This has led to delinquency, vandalism, and moral degradation. The immigrant population is mostly concentrated in sub urban regions of French cities. The largest of such concentration is in Paris followed by Marseille.

The French prison system reflects the deep social and ethnic divides roiling France and its European neighbours

African diaspora neighborhoods followed by Moroccan and Algerian neighborhoods see among the highest rates of crime in France and, in turn, bear the brunt of police violence, accentuated by ingrained racial attitudes. While the crime rate in African diaspora neighborhoods is because of the socio-economic factors, the crime rate and lawlessness in Muslim neighborhoods is linked to extremism, cultural values and identity. The outrage at Nahel’s death is a combination of both and must be seen within this context.

In the Paris region, public-sector employment vacancies were regarded as “undesirable” based on residential addresses and identity photographs. The divide and mistrust in the French society is visible through the funds raised for both Nahel and the policemen who shot him. By Tuesday afternoon, the fundraiser for the police officer had topped €1.5 million ($1.6 million), while that for Nahel had raised just over €380,000 ($414,000). More than 78,000 people had donated to support the police officer, while just over 20,000 had donated to support Nahel. The divergence in the funds raised shows how French society is divided and French multiculturalism is a failure.

The fears of native French should also be taken into account. Many of them are afraid of being labelled as racists, hence they never ventilate their opinion in the public. The funds (1.5 million and still counting) raised for the police officer who killed Nahel is a testimony to the fact that the silent majority is afraid of the challenges that are posed to the French society in the form of lawlessness, disrespect for the French ethos and values, and Islamic extremism. In some areas of France, police simply don’t exist. In their place, gangs armed with Kalashnikovs have been allowed to proliferate. Police is literally absent and too afraid to go into such areas to enforce the law. Another example of law and order going out of control was witnessed during the riots that rocked entire Europe when Morocco lost to Netherlands in the FIFA World Cup. The idea of injustice and xenophobia are not source of friction there but the clash of civilisational values of two parallel societies within France.

The Conundrum of Integration

In 2021, 10.3 per cent of France’s population was immigrants, a significant increase from 6.5 per cent in 1968. The origins of immigrants have diversified over the past 50 years. Immigrants, particularly those of non-European origins, face a less favourable labour market, lower wages, and less skilled jobs. Their living conditions, housing, and health are worse than the rest of the population. The second generation is closer to the situation of people with no direct migration background, with a 22 per cent lower standard of living compared to non-immigrant descendants.

However, inequalities remain in employment and housing conditions. Descendants of immigrants often experience discrimination, with 25 per cent of descendants aged between 18 and 59 experiencing unequal treatment in 2019-2020. One common indicator of the integration in multicultural societies is crime rate. Sociologists and Muslim leaders say the French prison system reflects the deep social and ethnic divides roiling France and its European neighbours, and that the Government’s social policies have isolated Muslims in impoverished suburbs with little hope of social advancement and even less respect for French authority.

The French Government does not collect data on race, religion, or ethnicity, making it difficult to estimate the makeup of prison populations. France has insoluble problems with part of its Muslim population, and its current skirmishes with radical Islam will ultimately be seen as a footnote. Nehal’s death is a wakeup call for policy makers in France to address the elephant in the room and take course correction measures regarding integration, radical Islam and police and constitutional reforms to prevent the civilisational conflict

within the French society.

Comments