A poignant scene in Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri’s The Kashmir Files shows a room full of petrified Kashmiri Pandits muzzling their cheer of ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’. They are doubtful about what the future holds for them in a land traumatised by Islamic terrorism. With their fates sealed at the altar of betrayal by their Muslim friends and neighbours, they can only hope that one day their expression of love for their motherland will not be shackled in fear and doubt. They wouldn’t have to pay a cruel price for being proud Indians. Most importantly, they won’t be punished for being what they are by birth—Hindus.

This scene is analogous to how a Hindu has been living in India. Proud of his Sanatani connection, yes, but not sure whether he should flaunt that feeling in circles, for fear of being derided for wearing his faith on his sleeves. Repressed for years in an ecosystem that would rather glorify the invaders, oppressors and colonisers of ancient India, he has learnt to live with, “It’s not fashionable to revel in Shiva bhakti or enjoying Hindu rituals and customs.” He daren’t chastise or correct those mocking Hindu culture, scripts and traditions. Pained about Hinduism always having to bear the brunt of ridicule in the garb of secularism or atheism, this silent majority has been waiting for winds of change to blow…

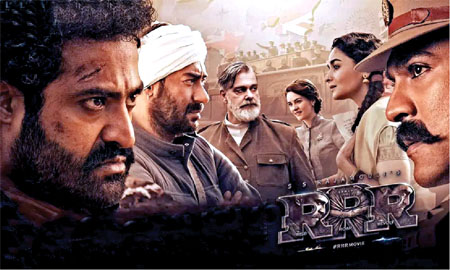

The victims in Agnihotri’s treatise (made on a modest budget of roughly Rs 15 crores, the worldwide collections have already crossed Rs 300 crores) on the 1990 Kashmiri Pandits genocide and exodus might be yearning to cry out ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ without any inhibition, but looks like that moment has arrived in Indian cinema, what with the celebration of Indic roots in important films. The soaring box office collections of SS Rajamouli’s Rise, Roar, Revolt (the pan-India film made on a fancy budget of over Rs 500 crores has been released in Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam as well as Hindi) bears testimony to the surge of nationalist sentiment in movies where Sanatani philosophies play a crucial role.

While Telugu cinema has largely carried a pro-India narrative, it is with Baahubali and RRR that the focus shifted on celebrating the quintessential Hindu vocabulary. Putting behind films such as Rahul Sankrityan’s Shyam Singha Roy (thoroughly inaccurate in portraying the Devadasi heritage, political and social history apart from insulting Hindu traditions), the heartfelt response to the latest money spinners might propel the Indian film industry to heed what the audience is thirsty for—movies based on un-whitewashed history and truth through narratives diametrically different from the anti-Hindu diatribe that Hindi filmmakers have stuck to for so long. If The Kashmir Files unraveled a dark episode of terror and politics, RRR has intensified the penchant to learn about lesser known national heroes. Rajamouli, lauded for his larger-than-life cinematic vision, picked relatively obscure Indian historical figures to weave a patriotic tale of grit, even as he paid a handsome tribute to everything gloriously Hindu.

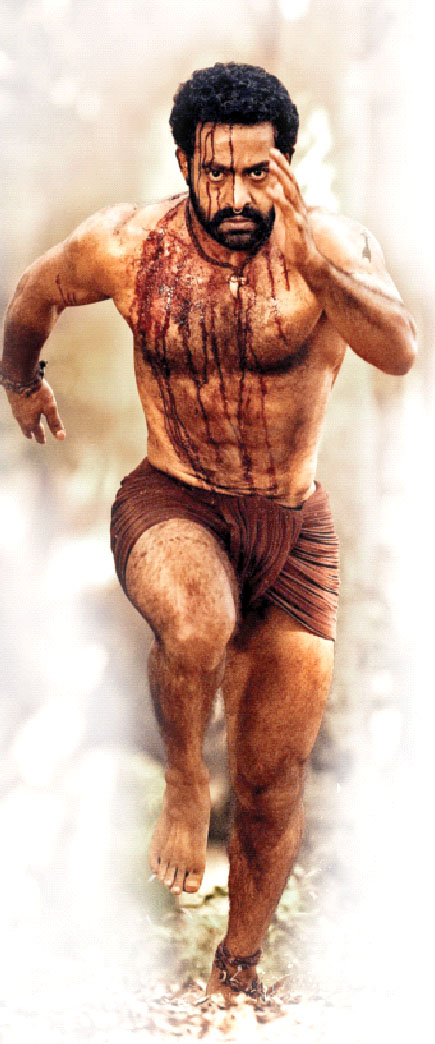

Who are Alluri Sitarama Raju and Komaram Bheem—India’s unsung heroes RRR’s protagonists are inspired by Alluri Sitarama Raju and Komaram Bheem, two revolutionaries from the Gond tribe that our NCERT texts never featured. Perhaps the idea was to never let Indians know about the uprisings that brewed in the villages of our country against the British. The Nehruvian historians hid from us the accounts of gallant heroes, whose love for their motherland was pure. Ram Charan gets to don the role of Sitarama Raju, who led the Rampa Rebellion (1922-24) against the Madras Forest Act, which prevented free movement of tribals in the forests and impacted their livelihoods. Under his leadership, the tribes fought a gruesome guerilla war, by attacking British armouries and police stations. Komaram Bheem, played by NT Rama Rao Jr, was another revolutionary who led a rebellion against the feudal Nizams of Hyderabad and the British Raj in the eastern part of the princely state during the 1930s, which culminated in the Telangana Rebellion of 1946. Interestingly, these heroes have been kept alive in the pages of regional history texts, unlike mainstream reading circles, so far occupied by Marxist and Left historians, who rather sing paeans on Tipu Sultan and his ilk.

Rajamouli’s work, despite taking vast creative liberties, doesn’t shift from the patriotic goalpost. While Baahubali’s magnificent theatrics painted a picture of our ancient Indian kings, his latest magnum opus presents heroes in a death-defying union of strength and strategy, two essential personality traits that icons such as Netaji, Shivaji Maharaj, Sardar Patel and Veer Savarkar inspired Indians to nurture. Swami Vivekananda had said, “Be a proud Hindu!” This reel world reignites that ardour emphatically.

Debunking the Gandhian Philosophy of Non-Violence

In an essential flashback to Alluri Rama Raju’s childhood, his father Venkata Rama Raju tells a fellow villager that if one gun scares a few attacking British soldiers away, one can only imagine the power of a combined armed attack in driving the imperial powers out of India. This line forms the underlying narrative of RRR, as it not only showcases the valiant push back two revolutionaries gave the colonists, but also debunks the flimsy rationale of passive resistance, propagated by a primal figure of our National Movement. This ideology was so flawed that it broke the spine of Indians, who were hypnotically hoodwinked to believe that non-violence would reap rewards. The stories of our brave Hindu kings who fought against the foreign invaders were craftily sidelined to mellow down the Kshatriya spirit in Indians.

We can’t help but acknowledge, as depicted by Agnihotri in his film, too, that the Pandits were not in a position to fight back when the Islamists bayed for their blood. Why couldn’t they recall the valour of Lalitaditya Muktapida, the powerful ruler of the Karkota dynasty, under whose rule subjects witnessed political expansion, economic prosperity and emergence of Kashmir as a centre of culture and scholarship!

With stories like RRR coming to the fore, it is evident that our freedom was hardly attained by quiet submission, as many politicians would have us believe. Rather, several revolutionaries earned it from the colonisers by sacrificing lives for their beloved Bharat. The last song of the film, apart from carrying a catchy beat given by MM Keeravani, makes a larger point with all the freedom fighters showcased in it. Netaji, Shivaji, Sardar Patel, and so many from down South are celebrated. Our school texts hardly dwelled on these prominent revolutionaries and more from the south. Whether it was done either to divide our united front or to alienate those heroes is anyone’s guess. Rajamouli, in a clever move, doesn’t bother to include one person in the song, too. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Does that mean this is an utterly irrelevant name by now!

Showcasing the true face of Invaders and Colonisers:

That the British tortured Indians can’t be denied but the sheer extent of the brutalities is what RRR harps at. The hypocrisy, betrayals, cold-bloodedness are drilled into our consciousness and eggs one to read up. In that, the film piques nationalist consciousness so that one never forgets our harrowed colonised past. The British came plunder, and ensured we were humiliated and enslaved. Along with distorting our Sanatani culture that was way more advanced than theirs ever could be, their toying with the tribal way of life and traditions was done to suit their greed. The film rubs that harsh fact in.

Here one must compare the girl Malli’s clothes before and after she is taken as a slave. Apart from separating her from her clan to serve their selfish needs, the British also rob her cultural identity. The film depicts the harmful effect of colonisation on indigenous identities through Malli’s attire. This inclusion is reminiscent of the case of Victoria Gouramma, the daughter of Chikka Virarajendra, the ruler of Coorg before he was deceptively deposed by the British under the command of James Stuart Fraser. A Wiki search on Gouramma would throw up ample visual proofs about how she dressed as a young princess in India, as against how her Indian identity was completely obviated once she was baptized under the care of her new guardians.

Through references to food, Agnihotri’s film also harps on the decline of cultural diversity under the influence of religious extremism. Living as ‘refugees’ in their own country, families like that of Pushkar Nath Pandit are not able to feed their children the wide range of unique dishes Kashmir is famous for. So, when Krishna Pandit is served authentic Kashmiri delicacies by the family he visits there for the first time, he is taken aback that he never heard of those preparations. While his grandfather speaks in his native tongue, the youngster isn’t proficient in it because they were displaced from their home, which was once a crucible of rich languages and traditions. Komaram Bheem prepared herbal medicine to treat Alluri’s hurt knees. This scene refers to the wholesome healing of Ayurveda, a science that failed to flourish in full steam when a colonised India fell prey to the chemical attack of Western allopathy.

Celebrating Sanatani Philosophies

Rajamouli infusing Hindu iconographies, giving importance to Indic heritage, itihaasa and Sanatan concepts is directed at making the Indian audience feel proud of their glorious past. Remember the shot of a strapping Prabhas carrying the Shivalinga on his shoulders. That vignette from Baahubali is etched in the audience’s mind till date. In RRR, too, the makers harp on Hindu iconography and the Panchabhoota. Alluri Ramaraju looks like a combination of Shri Ram and Arjun as he trains his arrow at the enemy. Komaram Bheem shoots his spears at the soldiers, reminding us of the Trishul. These are remarkable glorifications of our Sanatan heroes and their heroism. The audience is being nudged to celebrate his Hindu identity!

Rajamouli’s being highly influenced by Bharatiya itihaas as well as Mahabharata and Ramayana might not be explicitly evident in his narration, but the drift is pretty obvious. For instance, in one of the posters of RRR, Alluri is seen directing Bheem on how to train a gun, taking us back to the image of Shri Krishna directing Arjun in the art of strategic warfare. Then there is Bheem apologising to the tranquilised tiger, referring to the Hindu sentiment of treating animals with compassion. Indian tribes have always shared a beautiful conjunction with nature. That moment in the film is a tribute to that.

Music that evokes Patriotic Pride

Curtailing the noise churned out by Bollywood studios in the name of music, the symphony created by Keeravani for both Baahubali and RRR combines Indian classical notes, modern rock strains with Sanskrit lyrics. The song Ramam Raghavam elevates the character of Alluri to a spiritual level, even as he proves how alluring such music is today. While Agnihotri’s Hum Dekhenge is an anthem of awakening, RRR’s music is a heady mix of nationalistic fervor and Hindu pride. The compositions Komaram Bheemudu or Janani carry a strong undercurrent of patriotism. In Karan Johar’s Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, a Hindu girl’s dua is to Allah when she wants her father to unite with his lover. In Baahubali, Devasena croons a beautiful Kannaa Nidurinchara for Lord Krishna that lulls the handsome prince Baahubali to sleep. With Keeravani’s composition earning rave reviews, it is pretty clear what melody pleases the audience now.

Good Prevails over Evil

Our History books went on an overdrive to paint Indians always losing to invaders and imperialists. The purpose was to weaken our morale, by showing India and its legends in a bad light. In showing good triumphing over evil, Rajamouli delivers an ace. Yes, artistic license is taken for the sake of cinema but the denouement has its positive effects. Propaganda is minimized, because the narrative is trained against the atrocities of the British. Such blockbusters, despite the willing suspension of disbelief, pack in entertainment, great music, top class CGI, fantastic action and a rocking chemistry between lead characters that address the elephant in the room. That Sanatan Dharma or Hinduism is worth applauding and must not be ridiculed like how Rajkumar Hirani’s PK did.

The Pan-India Theory

With the audience shunning their propaganda filled content, Hindi film actors are drifting to the south for luck. This probably suits the Pan-India film perspective, where the larger audience is enthused to watch films that are much more than what Bollywood has made over the years. Rajamouli’s taking Alia Bhatt and Ajay Devgn shows his business acumen as well. Also, this move might make a largely ignorant mass notice our real icons. On the flip side though, the infiltration of Hindi producers and actors in Telugu films means the same jaded names hijacking the narrative. Karan Johar’s investment in Liger justifies his business aspirations, but the idea of an insipid Ananya Pandey teaming with Vijay Deverakonda isn’t half as exciting as the upcoming Pooja Hedge-Ram Charan starrer Acharya.

With Kriti Sanon playing Janaki in the upcoming mythological epic drama Adipurush, this trend of Hindi film actresses usurping roles in Telugu films seems to be growing. Hope the filmmakers maintain balance because there clearly can’t be a better Devasena than Anushka Shetty or a Sivagami Devi than Ramya Krishnan.

Looking Forward

With The Kashmir Files and RRR tapping the pulse of an audience ready for films carrying a nationalist, historic and Indic fervor, the stage is set for Mahesh Manjrekar’s directorial Swatantra Veer Savarkar starring Randeep Hooda in the pivotal role of the freedom fighter, social reformer, writer and poet. An icon whose role in the national movement has often been misconstrued, this could be a changeover in the Hindi film industry, if the makers create a work based on unbiased historical research as exemplary as historian Vikram Sampath’s exhaustive two-volume work on the political leader.

Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri’s next will focus on the Anti-Sikh riots of 1984. This would rattle the Leftists a wee more even as the filmmaker promises to deep dive into the events that took place after former Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination. Vipul Amrutlal Shah’s The Kerala Story, written and directed by Sudipto Sen will lay bare the horrifying truth of Kerala’s women being trafficked to the terror camps of ISIS, aided and abetted by People’s Front of India, a homegrown militant organisation.

The auspicious occasion of Mahashivratri in 2023 has been announced as the release date of Om Raut’s Adipurush, Pan-India cinematic take on the epic Ramayana, with Prabhas playing Raghava, Kriti Sanon Janaki, Saif Ali Khan Lankesh and Sunny Singh Lashmana. Credited for directing Tanhaji, Raut was piqued to make this Hindu mythological drama by combining stories from our ancient scriptures and modern CGI effects. Highly anticipated for championing Sanatan and Indic philosophies of Shri Ram, this film is already generating enough buzz. If this signifies change in the Indian film industry in tandem with Indic renaissance, filmmakers would be myopic not to be part of this wave!

Comments