The fact that the powerful imperialist forces of Britain had to bow down before the enduring grit and resilience of Indians is indisputable. However, the process that made it happen has been prone to misleading interpretations by many scholars of east and west alike. That the entire imperial rule was propelled by the idea of civilising the barbarians, that the British introduced India to modern technologies and political processes, that they ‘gave’ independence to India… books are replete with such mumbo-jumbo. Let us not forget that British colonisers were here for loot and plunder and were thrown out by the people of India who decided to settle with nothing short of swaraj.

Decolonisation of Bharat was a result of struggle of strong nationalist people and sentiments continuously confrontng the sly and oppressive British empire and its stooges. There was an unvarying spirit in the subcontinent that united people into one nation. It was coming together of various factors and forces that made it possible. One such extremely important factor that made this confluence possible in such a large and culturally different nation was the new communication technology: the telegraph, printing press, and the radio. The very means of communication that the British introduced to establish themselves firmly was undermined by the resilient Indians who acquired and propagated ideas and information using those means. All these gained momentum after the first war of independence in 1857.

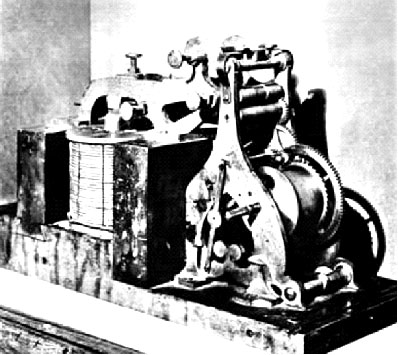

The British used telegraph in their colonies so as to increase their control over the land and its people. In Story of the Indian Telegraphs: A Century of Progress Krishnalal Shridharani quotes Dalhousie who wrote to a friend in 1854 about telegraph service between Calcutta and Bombay, “In less than one day the Government made communications which, before the telegraph was, would have taken a whole month – what a political reinforcement this is!” It was, indeed. But what they did not realise was the potential it held for the politically consciou Bharatiyas who matched their calibre one on one. Going by the British accounts, the telegraph played a vital role in controlling the situation during 1857. Post 1857, they rushed to build more telegraph lines. Several million telegrams, with runners to bear them to and from all corners, were delivered by a year. The cost of messaging was cheaper as compared to Europe or North America so it was an affordable and fast way to connect and spread information. Telagraph became a means of prompt and direct communication between India and London too. But interestingly, it also spread anti Britain news from far-off places thus undermining their status quo. The news of victory of Japan over Russia in 1905 stimulated nationalist movement to another level. Be it Swadeshi movement in Bengal, communication among various political leaders and associations within India or activities of political leaders, telegraph brought together Indians from different regions in an unprecedented manner. Revisiting the correspondences of political leaders of the time reveals that shorthand, sometimes cryptic messages, became definite means of communication of urgent messages.Thus the hopes that imperialists placed in the potential of telegraphy were significantly shattered in the face of its utility by the Indians.

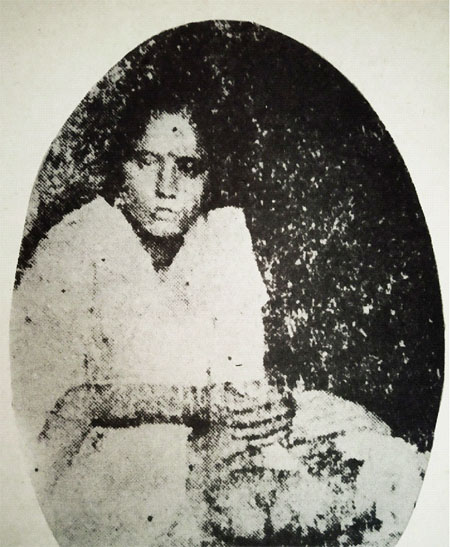

Unsung Heroes

Bhogeswari Phukanani

Bhogeswari Phukanani, was 60-years-old woman, in Barhampur area of Assam’s Nagoan district. Phukanani actively participated in the local protests against the British authorities as well as in women organisations in the area. She even encouraged her children to participate in the freedom movement.

On September 20, the procession started as per the plan, to hois the flag on the Nagon Police station. Bhogeswari Phukanani was leading the mob. As soon as they reached the police station, they were confronted by Captain Finch, he snatched the flag from Ratanmala’s hand, who fell down on earth. Furious by the disrespect to the national flag, Phukanani snatched the flag from his hand and hit his head with the pole of the flag.

Enraged by her actions, Captain Finch pulled out his revolver and fired at Bhogeswari Phukanani, who fell down to the ground. She succumbed to her injuries and died on September 20, 1942.

Similar or rather accentuated case was of the newspapers. Newspapers became the lifeline of communication during the struggle for independence. Post 1857, hundreds of newspapers, both in English and in Indian languages, started getting published in India. There were even more number of small printing presses. They conneceted people with each other and exposed not only the repressive policies of the Government but also the social malaise within. Fully aware of the potential of Indians to communicate, organize and challenge the authority of British, the Government passed the Vernacular Press Act of 1878 in order to censor newspapers published in Indian-languages. Those that didn’t abide by the regulations were either forcefully shut down or their machines and paper got confiscated. Interestingly, this law was not applicable to English-language newspapers so some editors escaped the horror by switching to English language. Newspapers (incitement to offenses) Act of 1908 and the Indian Press Law of 1910, were passed in response to the unrest and the Swadeshi movement. Any news that was likely “to bring into hatred or contempt His Majesty or the Government… or to incite disaffection toward His Majesty or the said Government…” was deemed illegal. Whereas, most of the British owned newspapers became mouthpieces for the government and its policies, Indian language newspapers and editors became the target of vilification. By 1919, around 350 printing presses and more than 300 newspapers were fined. Hundreds of presses and newspapers were prevented from even starting up. Incessant censorship and the gagging of the nationalist voices of newspapers only worsened the tension between the British and the freedom fighters. This repressive atmosphere stimulated the publication of underground newspapers and pamphlets rather than muffling the spirit. All Indian language newspapers reaching out to and connecting the voices of the public, openly condemned the repressive policies of the British.

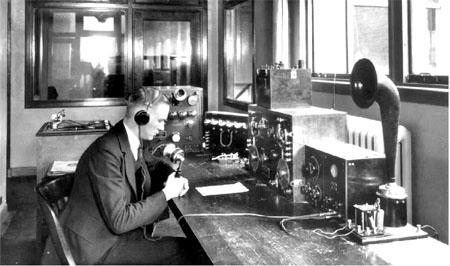

Voices of anti-colonial sentiments found even greater impetus through radio. The emergence of radio acted as a supporting tool for both the British administration and the freedom movement. Radio played an important role at the time when charismatic and media-aware leaders were gaining ground. Broadcasting started in the 1920s in India. British were so conscious of its potential to influence public opinion that they attempted to control it almost immediately. It was a general belief that monopoly over control of information would reinforce the authority of Britain as in other parts of Europe. It happened in Italy which created political consensus largely through broadcasting; Soviet Union used it to transmit revolutionary messages and during the nine-day General Strike in Britain in May 1926 radio came to the rescue of the ruling circles. The stage for development of radio in India was set between the two world wars and. During the Second World War, radio was used as part of the war strategy. Most warring sides, British, Germans, Italians were using the radio for propaganda predominantly in Hindustani in this region. There were three analogous situations that gave radio an advantage in the context of 1920-30 British India and anti-colonial agitation. Movements across the world for rights and freedom, immediate broadcast of the repressive policies and actions in the colonies and competing international broadcasting setting were major conditions that increased the popularity of radio. Once again radio proved to be a highly contested medium of communication. Its geopolitical potential to connect listeners was seen as a double-edged sword by the British. Censorship was imposed for radio in 1927 in principle. A blanket ban on the broadcasting of all controversial and political matters viz political speeches, lectures, anti- government programs etc was enforced. Here, even though the government was obliged to desist from the use of broadcast of the contents it denied to its political opponents, the shrewd British administrators kept for themselves an important loophole by which the Government had the discretion to preserve the right to use radio for the broadcasting of “correct information or to combat misrepresentations” in exceptional or critical circumstances. Underground radio networks gave voice to these choking regulations. Initially the reach of radio was very limited due to paucity of transmitters and inability to purchase radio sets. But for the political leaders, radio did make noise in right places with perfect amplitude. Eventually, communication through radio came to be used as tool of imperial domination as well as voice of the colonised much to the chagrin of the British.

Bharat was one of the most important of Britain’s colonial possessions that they meant to keep by all measures. The aftermath of 1857 pushed them to build better communication networks through telegraph, newspapers and radio. However, the use of the same communication technologies by the people of India during struggle for independence was totally unpredictable and baffling for them. The new communication technology that the British had instituted in India was designed to make their presence on the sub-continent gainful and lasting. In spite of all the ban and censorship, it undermined their colonial rule.

Comments