The Kerala Forests and Wildlife Department in its present website (History Section) admits that many of its records kept in its divisional office at Nilambur were attacked and burned down during the Mappila Lahala (Moplah uprising) of 1921.

To quote the Kerala Government’s website, “During ‘Mappila Lahala’, Forest officials were harassed and many of the forest buildings were burned and destroyed in 1921 – 22. One of the oldest collection of books and other authoritative records of forestry in Malabar kept in the Divisional Forest Office in Nilambur, were also destroyed during the ‘Mappila Lahala”

What was the interest of Khilafat volunteers in attacking the Nilambur forest office and burning records? There was absolutely no agrarian/tenancy disputes as propagated by Left lobbies in this forest area of south Malabar.

The Eranad—Walluvanad taluksin south Malabar were the prime zones, where the major riots took place before and in 1921. Charles Alexander Innes who compiled Malabar Gazetteer observes on Ernadtalukthat “nearly a third is hill, forest and jungle”. According to Malabar Deputy Collector C Gopalan Nair, Eranad is a tract made up of hills, clothed with forest which produces teak and other timbers. William Logan who authored Malabar Manual places Eranad as “overrun with woods, hills and mountains”. Some of the evergreen forests of Kerala, such as Silent Valley and Attapady Valley are located within Malabar. The Eranad-Walluvanad region in south Malabar was not much useful in good agriculture (except Palakkad) and communication due to hillocks, extensive forests and lack of cultivable alluvium. On the other hand, ginger cultivation was extensive in Eranad, the best quality cultivated at Kozhikode, while among gardens, pepper was grown mainly in the three northern taluks of the district. Pepper and ginger were purchased from inland Hindu and Christian producers by Moplahmerchants who routed these species to Kozhikode for export to west Asia and China.

But unlike north Malabar, south Malabar has more extensive forests with rich timber resources such as Nilambur, Kadalundi, Nedumkayam, Adayanpara, Amarambalam, Chathamporai, Nellikkutta, Valuvasserri, Erambadom, Kanakut, Muriat, Mangalasserri, Arimbrakkutta, Mannarghat, Walayar, Silent Valley, Attappady and Bolampatti.

The teak from Nilambur forests, was the preferred timber in the world. The forests of south Malabar are classified into Nilambur and Palakkad forest ranges. Nilmabur division comprised of Nilambur and Amarambalam ranges covering an area of 81,198 acres. The soil of the south Malabar region can be classified as sandy, laterite and hilly or forest deposit. These two taluks are extensively rich in forest resources, especially timber which was exported to west Asia and

Europe. Forests are located in Vazhikkadavu, Edakkara, Moothedam, Pothukkallu, Karulai, Kalikavu, Karuvarkundu, Nilambur, Mampad, Urungattiri, Perakamanna, areas of Nilambur and in Mankada, Vettathur, Kariavattum and Arakkuparamba of Perinthalmanna, all in south Malabar. The Palakkad division had two ranges Palakkad and Mannarghat covering an area of 112 140 acres.

Even Tipu Sultan who invaded Malabar, when desiring timber on his own account, paid an allowance to the Moplahs (who had absorbed the duties and functions of kannakaran, as well as janmi) based on the quantity of trees he cut. When the British came in contact with Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan in the wake of encounters, they understood the importance of teak and how Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan used teak timber for ship building purposes and exported teak to Arab countries and earned money.

By the early 18th century, Attappady forest region became the jenmom property of the Samutiri (Zamorin) of Kozhikode. The Samutiri entrusted the administration of this area to three Chieftains, Mannarghat Moopil Nair, Palat Krishna Menon and Eralpad Raja.

The control of Malabar came under British in 1792, in accordance with the treaty of Srirangapattinam. Colonial authorities noticed the valuable timber wealth of Malabar forests, and identified Nilambur teak as the best substitute of oak to build ships for British navy, since due to heavy utilisation, it was almost completely exhausted in England. In south India, the finest quality of teak from Malabar and Aanamallai was sent to Mumbai dockyard for ship building since the last decades of the second half of the eighteenth century. The southern forests of Malabar such as Walayar, Kollinghood, Kammala and Tenmalapuram forests in Paulgautecherry district and Ernad as well as the northern forests of Nedunganad and Nellatree were denuded to construct frigates and warships. Teak wood from Nilambur forest was used in the construction of Buckingham Palace, Kabba of Mecca, the interior of Rolls Royce car and RMS Titanic. When East India Company annexed Malabar, they set up a committee in 1805 with Major William Atkins and Alexander Mackonochy for a detailed survey of all accessible timber resources. Joseph Watson appointed as Conservator of Forests unified the provinces of Kanara and Malabar in the forest department to facilitate centralised timber trade for British

According to W G Farmer, Member, Bombay Bengal Joint Commission and Supervisor of Malabar, the timber forests in south Malabar were managed by temples. Before the British took control of Malabar in 1792, timber procurement for its export to west Asia was completely given to Mappilas by temple trusts. The Mappilas of Malabar employed several merchants who were employed in timber procurement. The trees in a particular region called coup are marked by a master carpenter and allowed to remain in a half cut stage for a less or longer period according to requirements of the merchant. The master carpenter was appointed by the Mappilas. The tree was cut off from the roots and dried on the stem. The wood cutters remained in the forests for months until the cutting season ended. The transport of the logs were also negotiated by the Mappilas. Finally the logs were taken to riversides and floated to market places such as Kallayi. The Beypore river which taps Nilambur and its surroundings, connects with Kallayi the second largest timber yard in the world. In Malabar, elephants were preferred to drag timber to the river edge and Nilambur is a major elephant sanctuary. Later, timber was floated down the Kottariver to Kottakkal and through Payyoli canal and Agalappuzha to Kallayi and down the Valarpattanam river in Kannur. The last phase of timber trade was performed by coast merchants majority of whom were also Mappilas.

The monopoly of Mappilla merchants on timber diminished after downfall of Mysorean Sultans and occupation of Malabar by British. In a petition filed in 1808 at the Zillah Court in Tellicherry by Chovvakkaran Moosa, principal Mappila business tycoon of Kannur, he claimed that the new regulations by British deprived Mappilla merchants of their ancient and customary rights in the forest.

It was Henry Valentine Conolly Malabar District Collector, who initiated in 1,848 teak plantations in Malabar which became a pioneering example of systematic forest management. This led to the establishment of a teak plantation in Nilambur, a part of Eranad Taluk in south Malabar district with a very extensive forest area. In 1840, Connolly suggested to the Government for the acquisition of 260 sq. miles of private forests in the Nilambur valley and Mappila merchants lost their monopoly. Conolly obtained the lease of forest land from the Zamorin of Kozhikode and his vassals in Malabar for initiating teak plantations.Although the exile of MambramThangal, the Sunni priest to west Asia is considered major reason for Conolly’s murder in 1855 by Moplah fanatics, his active intervention in teak plantations became a major hindrance for the Mappila teak tycoons. In 2018 it was reported that “it has been 163 years since Henry Valentine Conolly, the former Collector of Malabar, was killed by religious extremists” (Conolly’s Contributions Remembered in The Hindu Sept 11,. 2018).

Studies by SJayashanker, Deputy Director of Census Operations for Census of India, identifies settlements where large scale migration of Hindus took place during invasions of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan. These settlements which witnessed large Hindu migration were concentrated in Vadakara, Koilandi and Kozhikode taluks in Kozhikode district, Sulthan Batherry taluk in Wynadu district and Kathiroor and Etakkat in Kannur all in north Malabar. Eranadu, Thiroorangadi, Ponnani and Thirurtaluks in Malappuram district, Palakkad, as well as Talappili, Chavakkad and Thrissur in south Malabar, which are major regions where large scale migration of Hindus took place during Tipu’s invasion.

Due to this migration of landowning Hindus, Tipu’s army settled land revenue purposes with Mappila kanamdars, a fact which has been highlighted by William Logan. In south Malabar, the kanamdars were very often Mappilas. Due to the Hindu migration, it was Muslim kanamdars who in Tipu’s time had “considerably augmented their formerly more circumscribed possessions” and had become “the principal land-holders” in interior south Malabar. Michael Mann argues that this gap was filled by a calculable number of Mappilas who not only became landowners and improved their economic situation and social status, but also resulted in fierce conflicts with the traditional landed elite, who constituted Hindus.

In 1792, with success of British East India Company, the Hindus who underwent migration returned to Malabar to reclaim their rights on their land. The East India Company realised the trauma of Mappila resistance if land is returned and reclaimed by dispossessed Hindus. It was observed that this can cause violent outbreaks, from the part of the “Mapilla Kanamdars” of south Malabar who, during the period of Hindu jenmi depression and migration “habituated themselves to the ideas of independent tenure”. During Mysorean interlude, especially during Tipu’s invasion, Mappilas became proprietors of the land after the exodus of their masters. Logan also highlights that “from 1792 till 1802, the district was in a state of constant disturbance from rebellions and organised robberies, and in these the Mappilas took a conspicuous part”.

The Mappila kanamdars appropriated land and revenue when Malabar was under Tipu. According to Marxist scholar Conrad Wood, at least in a well-documented case, the interest of the Muslim kanamdars was linked with the fortunes of Tipu.

The temple managements in Malabar which owned extensive tracts of forest land, especially in Eranad and Walluvanad, became suspicious and also hostile to Mappilas after the Mysorean incursions. The Mappilas in Malabar provided man power and other facilities for the Mysore Sultans. The Mappilas of the rich Chuyot, Tazil and Kattale families, and their fifteen member gang accompanied by over two hundred people on January 8, 1852, attacked the house of KalliadNambiar, a wealthy landlord who owned an extensive and forested portion of Chirakkaltaluk, as narrated by William Logan. There was no former animosity with Nambiar for such an outbreak.

This incident led to strong resentment by Hindus who owned extensive forest land as part of the temple trust. H V Conolly observed that Hindus strongly objected to the introduction of Mappila settlers in their vicinity. Similarly, the Kavalappara family also managed forestland in Walluvanad, along with temples such as Puthukulangarakavu, Aryankavu, Trikkunyavu, Eruppa, Kunnakkattkavu and Mulamkunnu-kavu. They did not sympathise with the Mappilas who were prevented to settle in any of the amsams under the jurisdiction of the Kavalappara family, especially after Mysorean interlude. They were allowed to have a day's residence to attend the weekly market at Vaniyamkulam.

Further north, in Pathinalu Desam region, comprising the amsoms of Mootedath Madamba, Srikrishnapuram and Vellanazhi, the exclusion of Mappilas was almost as complete.

Trikkalayur was centre of large Moplah outbreaks in December 1884.They prayed at Churoth Mosque opposite the Trikkalayur Siva temple before the outbreaks. Another interesting fact is that Mappilas who organised for outbreaks at Trikkalayur belonged to Iruvetti, (Ariakode) and Edavanna (Tiruvali) which were timber trade centres.

Contemporary scholars such as Michael Mann argues that by the last decade of the eighteenth century, invasion of Tipu Sultan forced a large proportion of Hindu landholders to leave Malabar and that this gap was filled by a calculable number of Mappilas who not only became landowners but also resulted in fierce conflicts with the traditional landed elite and open rebellion by Kanamdars of south Malabar. Studies show that the fierce encounters that took place ‘before 1921’ were forest/timber zones such as Manjeri, Nilambur, Kolathur, Mattannur, Chirakkal, Irikkur, Kottayam and Eranadu associated with Hindu aristocracies who managed such forest lands, and those who marshaled the riots were wealthy Mappila families.

This has much importance since the large tracts of forest lands in Malabar, where the riots took place were only managed and not privately owned by Hindu landlords who were vassals of the Samutiri, such as Nilambur Tirumulpad, Eralpad Raja, Edavanna Kovilakam, Mannarkkad Muppil Nayar, Palat Krishna Menon, Trikkalayur Krangad Ashtamurti Nambudiripad and Wandur Nambudiripad.

“I have puzzled for twenty-five years why outbreaks occur within fifteen miles of Pandalur Hill and cannot profess to solve it”, was the lamentation of H M Winterbotham in a report on the outbreak of 1896 (Report of Winterbotham May 5, 1896 Madras Judicial Proceedings, No 1567 September 30, 1896). As CA Innes observed, Pandalur was one of the densely forested areas in Eranad.

Left scholars such as Kathleen Gough, DN Dhanagare and K N P anikkar presented Muslim Mappilla tenants, as victims of rack-renting, evictions, and famine with the spread of cash crop farming and the disruption of their formerly stable tenancies, which eventually lead to uprisings against the landlord and British government.

Conrad Wood, himself a Marxist scholar admitted on Malabar riots that explaining these outbreaks as mere anti-jenmi manifestations posed difficult problems with which, Malabar collectors most responsive to tenant grievance gained only “very partial success”. Wood also raised a serious question. If Hindu tenants and labourers (in Malabar) admittedly suffered quite as much, if not more from the socio economic system, why were outbreaks confined to the Muslim community? Wood’s observations prompt us to raise another serious question in this context. Why there did not occur a single uprising, or even slightest protest by “poor and exploited Mappila peasants” against “wealthy Mappila landlords” in Malabar such as Korangonatha Unyen, Vadakate Mugaree, Athan Moyeen Kurikkal, Iripattadathil Rayen, Chooryot Tazil, Kattale Moplahs, Vallapillangath Hasan Kutty, Kunyali and Muhammad Kutty. The Left historians have conveniently ignored such a class and suppressed this fact to interpret the outbreaks and riots in Malabar according to their political convenience.

World's oldest teak plantation in Nilambur. Mappilas timber traders had an eye on teak farms owned by Hindus

During the Colonial Period, timber merchant companies by Mappilas emerged in Malabar. They made contract with the British railway authorities to construct several railway tracts using timber. Some of the timber companies owned by prominent Mappilas included Khan Bahadur Arakkal Koyatty-Hajis-Timber Company, Kamantekath Kunhahammed Hajis timber company and Khan Bhadur V K Kunhikkammu Haji Timber Company. The 66 km long Nilambur—Shornur rail line in Malappuram was constructed in 1925-27 by South Indian Railway Company under British at a cost of 70 lakhs.

Fifty riots took place before 1921 in which Hindus lost life and property. The ghastly murders such as that of Kulathur Warrier in 1851, slaughter of eighteen members of Kalathil family in 1852 at Mattannur in Kottayamtaluk, attack on KuliatAnandan of Irikkur in Kannur in 1852, are some instances in these fifty riots.

The first and major riot of 1921 began at Pukkottur which lies adjacent to Nilambur timber zone, in Malabar, accommodating the richest teak and timber plantations in the world. Over two hundred Mappilas armed with guns and swords assembled at Pukkottur on a rumour that the Thirurangady mosque has been destroyed and hence they were determined to encounter the army. They marched towards Nilambur Kovilakamand night murdered sixteen members of the royal family which included twelve males, two women and two children. It was not tenancy issues or peasant disputes, but widespread rumours regarding destruction of Thirurangady mosque that led to the outbreak and carnage of Hindus.

The Koyappathod was a traditional Mappila family having immense land and wealth associated with timber business founded by Muhammed Sildar. His grandson son Ahamed Kutty also became a big timber merchant and the proprietor of Malabar Timber Supply Corporation. He was arrested for involvement in the 1921 Mappila riots.

RH Hitchcock,the first Commandant of the Malabar Special Force, highlights the prominence of timber agents and merchants in 1921 riots. He discusses the role of “major rebel leader Amakundan Mammad, at one time an agent of a big Angadipuram timber merchant and also a substantial cultivator in the eastern part of the “fanatic zone”, who was also a big kanamdar of the type which had been so prominent in anti-jenmi and anti-British manifestations in the past”.

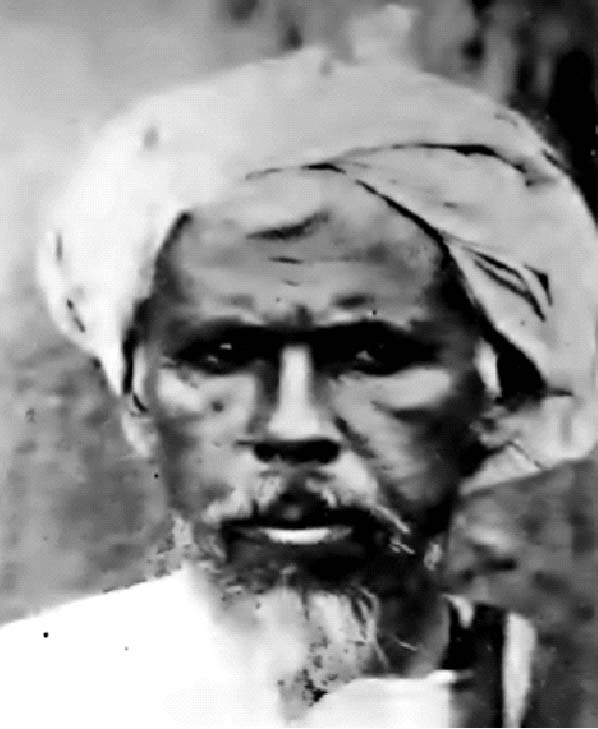

Ali Musaliar, chief of Mappila army

Leading national Khilafat leaders in Mumbai such as Mian Mohammad Haji Jan Mohammad Chotani were international timber merchants.Timber merchants in Mumbai had close links with Malabar timber market. The Central Khilafat Committee was constituted in 1919 at Mumbai with Mian Mohammad Haji Jan Mohammad Chotani (1873-1932) trader and premier timber merchant. Nasir Mulla is the patriarch of a prosperous family business for five generations who have dominated the timber trade in Mumbai. Ahmed Latif and Company Abdul Ral, were other Mumbai-based timber traders.

From the beginning of the World Wars ie 1914 to 1945, the era before passing of forestation Bill, there was an escalation in the number of timber traders in Malabar. Besides Bayon Chacooty and Chacora Moussa, some of the native timber companies in Malabar during this period include the Khan Bahadur Arakkal Koyatty Haji, Khan Sahib Unnikkammu Sahib, Kamantakath Kunjahammed Koya, Jifri and Company and Baramies who were the noted teak merchants of that period. Khan Bahadur Ali Baramy major timber merchant of Kozhikkode was awarded Khan Bahadur title in 1926 by British Government.

The Khilafat gave full support to British as long as Britain maintained friendly ties with Caliph of Turkey. Muslim leaders of Malabar on September 1, 1914 assembled at Himayathul Islam Sabha Hall near Kozhikode and appealed Mappilas to join hands with Britain and make prayers by offering Fathihah in each mosque for their success. When Hagia Sophia issue came up in Europe with establishment of Hagia Sophia Redemption Committee and Britain taking the lead to reconvert the AyaSofya Mosque back into a Cathedral, the Khilafat turned hostile towards Britain.

The Muslim League in Kerala was launched by prominent timber merchants of Malabar. In I969, in accordance to the demands of the Muslim League in Kerala and as a reward for its political support, the Communist Government of EMS Namboodiripad carved out the new, Malappuram district accommodating major timber regions which included the world famous Nilambur teak zone.

Comments