The rich historicity content in the judgement is matched only by its jurisprudential richness and cogent pragmatics. Given the breadth and diversity in viewpoints over the judgement, even within those with almost matching worldviews, it is imperative to objectively decipher this decision and analyse its Politico-Dharmic implications

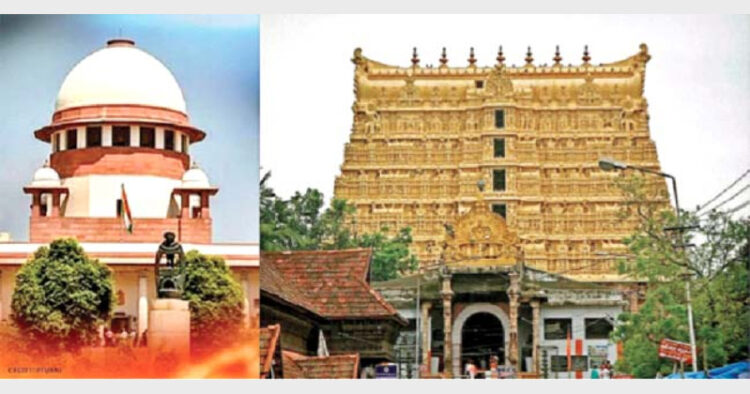

From being hailed as a harbinger of Hindu renaissance to being termed as an insult inflicted on injured Hindu cause, the two hundred eighteen-page apex court verdict in the matter of Sree Padmanabha Swamy Temple, Thiruvananthapuram (“Great Temple”) has evoked strong and divergent responses. Being perceived as favourable to the royalty, it has been criticised as a resurrection of feudalism. A section within the Dharmic fold has termed the verdict as deeply disappointing as it disallows the denominational status to the temple. Yet another section sees nothing objectionable in terming the Great Temple as a ‘public temple’. In fact, some sections see this as a golden median future model of regulating the Hindu temples. Given the breadth and diversity in viewpoints, even within those with almost matching worldviews, it is imperative to objectively decipher this decision and analyse its Politico-Dharmic implications.

Unlike most temple disputes, this litigation trail is of recent origin. In 2010, Uthradam Thirunal Marthanda Varma, younger brother of Sree Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma (1912-1991) the former Ruler of State of Travancore, approached the Kerala High Court apropos the Great Temple. His case First off, on the ground that Travancore-Cochin Hindu Religious Institutions Act, 1950 (“TC Act”) recognised only the Ruler and had no provision for succession. The Court held – successors of the last Ruler including his brother, do not fall within the definition of “Ruler” under Article 366(22) of the Constitution; moreover, after the Twenty-Sixth Constitutional Amendment of 1971, even the President of the Republic too ceases to have authority to recognise any person as the Ruler of any State or as a successor of such Ruler.

Being unsuited thus, in appeal before the Supreme Court, Marthanda Varma sets up his case on his succession to Shebaitship (Trusteeship) and succeeded. The apex court, recognising the heritable rights of the royal family to Shebaitship, has held that as per the TC Act, the Ruler had the power of appointing the Executive Officer and of forming the Advisory Committee, and the rights are heritable by the Ruler’s successor. The verdict says that Shebaitship has devolved on to the Ruler’s family by virtue of governing principles of succession and custom.

The fine print of this judgement is as significant as its core content. At the end of all the arguments, the Ruler’s family submitted a note in which the Ruler’s powers were delegated to two committees – Administrative Committee and an Advisory Committee. In the operative portion of the judgement, the Court records its acceptance of this note with some modifications as its composition. The District Judge, Thiruvananthapuram will be the ex-officio Chairman of Administrative Committee composed of a nominee of the Ruler family and that of State and Central Governments. Likewise, the Advisory Committee will be chaired by a retired High Court Judge nominated by the Chief Justice of the Kerala High Court with one eminent person to be nominated by the Trustee; and a reputed Chartered Accountant to be nominated by the Chairperson in consultation with the Trustee.

The Court has also directed the Committees to order for the audit of the past 25 years. The decision as to whether Kallara-B is to be opened for the purpose of inventorisation is left to the best judgement of the Committees constituted as above. The Court also directed the Committees to file the audited accounts and the Balance Sheet with the office of the Accountant General for the State, every year.

A deeper deliberation would reveal that the Supreme Court has balanced the two extremist positions and treaded the golden middle path

A deeper deliberation would reveal that the Supreme Court has balanced the two extremist positions and treaded the golden middle path. One extremist view is the one espoused those claiming the Big Temple to be a denominational temple. They argued for absolute autonomy without any democratic representation. This unhindered path with no checks and balances is not just opposed to democratic values but also to the cause of Dharma. The Communists led by CPM and Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP) hold the other extreme view of totalitarian state control. Through their political stooges and trade unions, the Left tried to acquire and sabotage the Dharmic institution.

The Supreme Court has clearly and convincingly isolated the isolationists and upheld the true Hindu Dharmic spirit, which is deeply democratic and representative. All dictatorial and lopsided forced and tendencies have been firmly dealt with. The forces on the fringe have been aptly side-lined and subdued.

In this entire episode, the conduct of the royal family of Kerala has been exemplary. Even though the TC Act empowers them with administrative control of the temple, the royalty has volunteered in constituting the Committees for advisory and administrative functions. On their own volition, they have ensured that their role remains remote and representative. More importantly, the Court has not directly imposed any fiscal enquiry but instead has directed the Committee to order an audit through its own appointee auditors. This is the best possible blend of autonomy with accountability and synchronous with the highest Hindu traditions of transparency and righteousness. Those criticising the verdict as feudal and retrograde ignore the sacrifice of royalty in opting for representative governance and acceding to the toughest test of transparency to which the institution has been put into. The royalty never opposed the suggestion of the Amicus Curie for an audit of past twenty-five years of temple accounts. Thus, it was embedded in the decision almost with mutual consent. Those opposing the judgement with a royalist skew conveniently and entirely forget this aspect.

The Court has consciously isolated itself from the denominational argument. Since its proponents laid no factual or evidentiary edifice at the trial phase, the Court rightly refused to go into this novel factual proposition. Denominational aspect is to be proved in trial and cannot be declared by at the apex court based on pleadings and arguments. It is trite law that appellate courts do not enter into factual controversies. So, the apex court decision is totally sound on this count.

The Court has consciously isolated itself from the denominational argument. Since its proponents laid no factual or evidentiary edifice at the trial phase, the Court rightly refused to go into this novel factual proposition

Independent of its rich and cogent jurisprudential content, this judgement is pathbreaking for innumerable reasons. The verdict and the selfless conduct of the royalty that enabled it – both lay down a unique model not just of temple management but Dharmic institutional governance in general. The mode and model are quintessentially democratic – blended with accountability and autonomy– that call for wider emulation, of course by factoring subjective realities of every temple regime. The democratic and transparency quotient has always been the hallmark of Hindu institutional governance structure, and the Court has rightly endorsed it with a sound jurisprudential basis.

The mainstream media has completely ignored a vital aspect that Court has upheld the heritability of Shebaitship (Trusteeship) the royal family on a deep moralistic and spiritualist ground and not on the status as erstwhile Rulers. The Court records through its Amicus that in 1750 AD, the entire State of Travancore was gifted to this Deity by a Deed and the Ruler became the servant of the Lord, calling themselves as Padmanabhadasa. It is also documented that many of the Maharajas were great composers of shlokas as well as music. In fact, many of the Rulers were protectors of the Vedas and the Vedic tradition. The Shebaitship (Trusteeship) of the Rulers’ family is a function of their virtuous service to the Deity and prevalent custom spanning over several generations. The Court is not agnostic to custom yet fully conscious that the custom has to manifest in modern times through a democratic medium and modus.

Some least noticed provisions of the Constitution like Article 290-A under which a charge forty-six lakhs and fifty thousand rupees shall be charged on, and paid out of, the Consolidated Fund of the State of Kerala every year to the Travancore Devaswom Fund find a mention in the judgement. The works of VP Menon, legendary lieutenant of Sardar Patel and Advisor to the Government in the Ministry of States, are extensively quoted and relied upon for arriving at the judgement. The rich historicity content in the judgement is matched only by its jurisprudential richness and cogent pragmatics.

(The author is a practising advocate and founder of Navayana Law Offices)

Comments