Since its creation as a free port in the mid-nineteenth century, Hong Kong’s raison d’être has been to aid a middleman between China and the rest of the world. The opening up of China during the late 1970s and the advancement of globalization further boosted this role and resoluteHong Kong’s position in the international division of labour (Augustin-Jean 2005; Zhao et al. 2012). Nevertheless, in recent years, Hong Kong’s role as a (business) hub has been slightly affected by China’s changing position in the world economy. This can be realised in the evolution of four critical rudiments of the Hong Kong economy, which have played a vital role in its function as an intermediary between China and the world on the one hand and as a global city on the other: (1) Foreign Direct Investments (FDI); (2) trade and logistics; (3) finance; and (4) tourism – the last three having been acknowledged ‘pillar industries’ by the Hong Kong government during 2002–2003.

Hong Kong’s manufacturers, who relocated their production of toys, electronics, textiles and plastics to factories in mainland China three decades ago, are on the move again.

This time, they are moving their production lines to Malaysia, Vietnam and lower-cost economies in Southeast Asia to dodge rising wages and land costs, and in search of safe havens from the intensifying trade war between US and China, said by the representative of 150 manufacturers with a combined workforce of 1 million and HK$200 billion (US$25.5 billion) in annual production.

In 2019, US companies had the world’s most significant number of regional headquarters in Hong Kong i.e. 278 (18% of the city’s total of 1,541, although that number was down 4 per cent from a year earlier). In total, there are about 1,300 American companies in Hong Kong.

After the historic virtual summit between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who concluded nine agreements including a Mutual Logistics Support Agreement (MLSA) and issued a joint statement on a “Shared Vision for Maritime Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.”, the QUAD coalition is ready. BecauseIndia is ready to allow Australia to join the annual trilateral Malabar naval exercise involving India-Japan-USA.

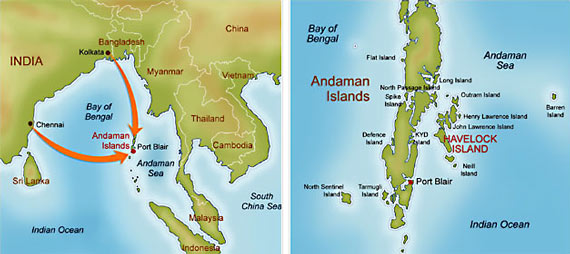

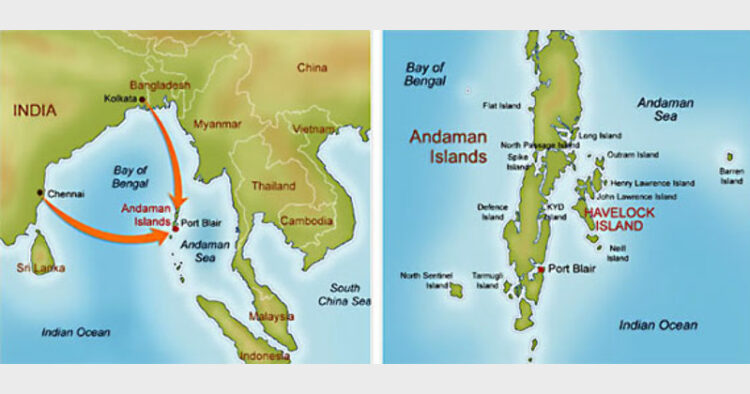

The QUAD coalition should also provide the replacement of Hong-Kong and permanent mechanism to solve South-China sea problem. In this regard, the Andaman is one of the best available options because of its proximity to the Malacca Straits and its geopolitical demography. Today over one-third of world trade and one-half of the world’s oil shipments transit the Malacca Straits, including 80 per cent of Japan’s oil imports, 80 per cent of China’s oil imports, and 90 per cent of South Korea’s oil imports. Numerous LNG tankers destined for Japan and South Korea, the two largest LNG importers, also traverse the waterway.

After attaining independence from Britain and Malaysia, Singapore concentrated its economy seaward, using its natural deepwater port on the world’s busiest shipping way to build a flourishing transhipment hub. Singapore capitalized in port infrastructure, while the rise of containerization set the maritime city-state on a remarkable growth path. Moreover, Singapore constructed one of the world’s most wide-ranging maritime innovation clusters, offering maritime support services ranging from bunkering to ship repair to maritime arbitration.

However, Singapore is not alone among flourishing seaports on the Malacca Straits. The Port of Tanjung Pelepas, situated in Malaysia’s Johor province, opened in 2000 as a direct competitor to nearby Singapore. Maersk established primary container operations in Tanjung Pelepas, in part, to pressure the Port of Singapore to lower container handling prices. Malaysia’s Port Klang is another major container hub on the Malacca Straits, serving the economic zone surrounding Kuala Lumpur.

After US withdrawal of special status to Hong Kong, the world needs new free port and financial hub in Asia, the existing options like Singapore, Malaysia may not be able to provide a base to all the exiting companies and business from Hong-Kong. Thus, the Andaman can not only accommodate the shifting companies from Hong-Kong but also diminish the container handling prices by reducing the burden from existing ports like Singapore and Malaysia. Further, the Andaman can become intermediary between QUAD and the world on the one hand and as India’s global city on the other based on following four pillars: (1) Foreign Direct Investments (FDI); (2) trade and logistics; (3) finance; and (4) tourism.

(The writer is the Honorary fellow at Global Governance Institute, London and Pentland-Churchill scholar for Global Public Policy leadership at New York University (NYU) & University College London (UCL))

Comments