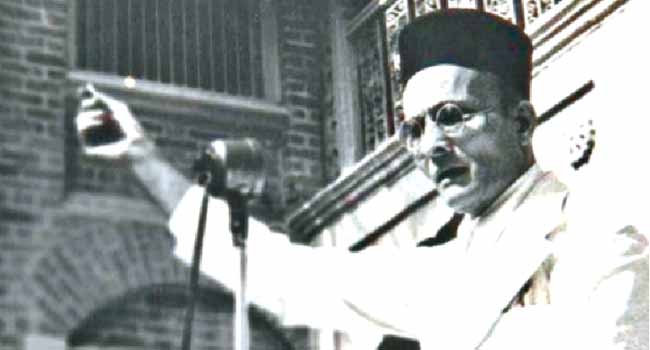

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar has been referred again and again in the contemporary political discourse to attack his articulation of Hindutva. Without understanding his views in totality and actions in entirety, one cannot understand the meaning of being Savarkar and get the complete picture of India’s struggle for Independence, writes renowned historian Prof. Raghuvendra Tanwar in this four part series

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar had called for and demanded complete freedom from British rule almost 20 years before a similar demand was raised by the Indian National Congress. In this sense as his first important biographer, Dhananjay Keer had put it: “His life removes the wrong impression …that the Indian freedom movement started with Gandhi and Nehru.” Savarkar spent almost 30 years of his 83 years of life in the prisons of British and free India. Of these over 10 years were in the notorious Cellular prisons of Port Blair. The physical and mental torture that he was made to undergo particularly in the Andamans, place him among those that paid the heaviest price in the fight for India’s freedom.

On Savarkar’s death (February 26, 1966) The Tribune dedicated an obituary editorial: “…the younger generation is not likely to know much about the heroic part played in the early years of the century to make India free… (he) was a born revolutionary …it was such stuff that India’s early leaders were made of …the present generation of Indians can hardly do better than cherish their memory…”

While presenting an overview of Savarkar’s contribution to India’s struggle for freedom this article examines and explains the importance of his views in the context of the revolutionary movement. It argues that it was this aggressively anti-British approach that actually weakened the spirit of the colonial administrative system. On the face of it, the colonial rulers appear to have got an upper hand over the revolutionaries, but observe carefully, it is easy to understand that fear, and anxiety had set in among the British. A worried ruling hierchy went on to become increasingly oppressive – one mistake followed another. The more force with which the British reacted to the voices of freedom, be it the Jallianwala Bagh or the long list of revolutionary heroes that took to the gallows, the more certain the exit of the British from India had become.

The article questions the manner in which the revolutionary point of view as raised by men and women like Savarkar has been downplayed and understated. It is argued that the length and severity of punishment given by the British to men like Savarkar was always in proportion to the level of threat that was posed by the individual concerned. Should it come as surprise that when Savarkar reached the cellular jail to begin his long sentence, he was the only prisoner that was given a dress that had a ‘D’ inscribed on it – standing for ‘dangerous’. How have some names been made to disappear from the pages of mainstream history?

Memories, contributions and importance as we know, can be cherished only if they are kept alive or retained in spot light. In a country the size of India and the vastness of its population, the role of textbooks prescribed by major national and state educational boards for example assume great importance because, what goes into the making of these curriculums assumes the form of a mainstream narrative. This happens because a prescribed story or version is read across the country by millions of school and college passing out students. The mainstream narrative or what is made to appear as mainstream narrative as such leaves lasting impressions.

‘The Story of Civilization’ was published by the National Council of Educational Research & Training (NCERT) in 1978 as a textbook for the Secondary schools. Its Vol. II was prescribed for class X, which in India is a key stage in a students’ life. Chapter 15 in this volume is titled, ‘India’s Struggle for Freedom’. The chapter contains 25 references to Jawaharlal Nehru, with six photos of Nehru. The name Mahatma Gandhi appears 17 times and has two photos of Gandhi. The name Subhash Bose is mentioned six times with one photo. The name of Balgangadhar Tilak appears 3 times with no photo. The name of Vinayak Savarkar like so many others finds no mention – not even once.

Savarkar is a name that is interwoven in the story of India’s struggle for freedom, particularly the history of the great Indian revolutionary movement. Likewise, if one were to study the history of the social reform movement in Maharashtra, Savarkar, even though was not from the same background as Mahatma Phule or Bhimrao Ambedkar, yet he appears a part of the same chain – the same link. Throughout his life, indeed at every stage Savarkar fought against the barriers of caste and its ills. Savarkar was a complete rationalist; he condemned strongly anything that drew its cause of acceptance from superstition. He took great pride in India’s historical legacy of culture, art, literature, yet, he wanted the contents of even the ancient scriptures for example, to be tested on the scales of science end rationality.

Savarkar was the first Indian to be rusticated from a government aided college, the first to set torch to foreign clothes, he was also the first Indian to tell the world that India would fight to the end, to extinguish colonial rule. Perhaps with the exception of Lokmanya Tilak and a few of the great revolutionaries no other Indian was made to suffer the rigours of jail by the British more than Savarkar. Of the conditions in the notorious Andaman jail, it was said at the time that, 6 months in the Andaman jail were far worse and more rigorous than 10 years in a British jail on the Indian mainland. Savarkar was in the Andaman jail for over 10 years.

One has only to read Savarkar’s, The Indian War of Independence: 1857, to understand his mind on the issue of how important he considered Hindu-Muslim relations and perhaps to appreciate that an individual’s faith and belief did not in any way influence his political philosophy. Savarkar believed in an India that stretched from the River Indus to the ocean. Anything that even remotely contained the possibility of dividing what he believed was the ‘natural’ Motherland was not acceptable to him.

Savarkar’s political philosophy rested on the simple principle of integrity, unity and strength of the ‘Motherland’, a term he often used. With this objective, he expected all citizens, irrespective of being a majority or minority to be committed to this cause. It was only natural for him to distrust those who talked of a separate homeland that would have to be created by partitioning India. That the Muslim League posed the first major threat to a united India is what made Savarkar distrust sections of the Muslim population. He refused to accept the concept of the partition of India (1947) or that it was the only way to ensure freedom for India from British rule. For him, the division of the country on the basis of faith was no option, it should not even have been considered, leave alone being conceded. He had mellowed down greatly as age caught up, but he was unable to forget or forgive those who had enabled the partition of his ‘Motherland’. This explains to a great extent his political differences with Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress as a party.

To understand Savarkar’s intellect, his life and work at length, one would have to study his important writings. He wrote The Indian War of Independence: 1857 (526 pages) in 1906-07 when he was just about 24 years of age. He followed this up with Hindu Pad-Padashahi; Hindu Rashtriya Darshan; Essentials of Hindutva and of course My Transportation For Life. He wrote extensively in Marathi and also for newspapers. His Letters From the Andamans, are a classic. Then there is, Epochs From Indian History; Dedication to Martyrs of 1857. He was a great admirer of the Sikh Gurus, and learnt Gurumukhi to read the Adi Granth, Pant Prakash, and Vichitra Natak. At about the same time he translated into Marathi the great Italian hero of unification, Mazzini’s, autobiography.

Early Life

Savarkar was born in the Village of Bhagur (near Nashik) on 28 May, 1883. He was one of three sons and a daughter born to Damodarpant Savarkar and Radhabai. The family was well off by standards of the time. Savarkar lost his mother to cholera (1898) and his father and uncle in the following year to plague. He too suffered an attack of small pox while his brother Narayan was lucky to survive an attack of plague. The entire region of the then Bombay province was in extreme turmoil. Famine, plague, British atrocities were all common place. It was around this time that the Chapekar brothers shot dead the British Plague Commissioner Rand and another officer Ayerst (22 June, 1897). Damodarpant Chapekar embraced the gallows on 18 April, 1898. The great Balgangadhar Tilak too was arrested on charges of seditious writings. In the years to come, Savarkar would take pride in being counted as one of Tilak’s greatest admirers and followers.

Mitra Mela & Abhinav Bharat

This was the kind of surcharged atmosphere in which Savarkar and a small likeminded group founded (1 January 1900) the ‘Mitra Mela’ or Friends Union. The agendas of the Mitra Mela and their basic approach towards the course that the fight for freedom should take had alarmed the government. Vikram Sampath, in his outstanding biography of Savarkar cites him in these early days : ‘He opined that there was no point merely cutting leaves of a poisonous tree one had to strike at the root to dismantle it for such a task one needed an axe and the person wielding it would have to risk his life…’

It was this basic difference in approach with regard to fighting British rule in India that would repeatedly make Savarkar come in confrontation with the Congress and its leadership. In Savarkar’s scheme of things, there was no place for petitions and pleadings or of displaying loyalty to the British crown : ‘Why would you honour someone who has made your mother a slave’.

In 1904 the Mitra Mela was renamed as Abhinav Bharat. Every member was required to take on oath:

Vande Mataram (Salutations to the Mother!)

In the name of God,

In the name of Bharat Mata,

In the name of all the martyrs that have shed their blood for Bharat Mata,

By the love innate in all men and women, that I bear to the land of my birth,

Wherein lie the sacred ashes of my forefathers, and which is the cradle of my children.

By the tears of the countless mothers for their children whom the foreigner has enslaved, imprisoned, tortured and killed,

I…

Convinced that without Absolute Political Independence or Swarajya my country can never rise to the exalted position among the nations of the earth which is Her due,

And convinced also that that Swarajya can never be attained except by the waging of a bloody and relentless war against the Foreigner, solemnly and sincerely swear that I shall from this moment do everything in my power to fight for Independence and place the Lotus Crown of Swaraj on the head of my Mother;

And with this object, I join the Abhinav Bharat, the Revolutionary Society of all Hindustan, and swear that I shall ever be true and faithful to this, my solemn Oath, and that I shall obey the orders of this organization (body);

If I betray the whole or any part of this solemn Oath, or if I betray this

organization (body) or any other working with a similar object, May I be doomed to the fate of a perjurer!

The Abhinav Bharat not only committed itself to the goal of a ‘free India’ but also to reaching the goal at any cost, even if it meant an armed revolution. It is this that made Savarkar stand out in British eyes as enemy number one.

Some years later when the trial of the Jackson murder case (Nashik conspiracy) took place the judge quoted at length on the danger from the Abhinava Bharat. The Tribune cited this judgment:

“It is by no means unusual to find the existence of societies aiming at the attainment of independence or Swarajya… prior to 1906 an association of young men existed in Nashik under the leadership of Ganesh and Vinayak Savarkar known as Mitra Mela… exciting songs were prepared for Ganapati and Shivaji festivals… biographies of patriotic revolutionaries were read, particular favourities being Mazzini, Shivaji and Ramdev… speeches were made for rising against the British and collection of arms and ammunition. …Vinayak Savarkar had been the most active and stimulating… Mitra Mela had developed or given birth to Abhinava Bharat or young Indian Society… objects were revolutionary.. aim of its members was to be ready for war… the book of verses composed by members was known as Laghu Abhinava Bharat Mata…”

Savarkar joined Poona’s (Pune’s) Fergusson College in 1902. By now, he was an established writer and spellbinding orator. Almost immediately on joining the college he started organising and spreading his anti-British and revolutionary ideas and programmes. He did these both secretly and even openly in the form of a hand written weekly journal, the ‘Aryan Weekly’. He wrote on literature, history, patriotism. Many of these articles were published by important newspapers of the time. One of his outstanding such article was titled, ‘Saptapadi’. In this, he discussed the different stages though which a ‘subject’ nation is forced to move. Just as he mastered the Indian epics, he was equally familiar with Shakespeare. He was in particular fascinated by Milton’s, Paradise Lost. Not surprisingly, his essay on Ramayana was as much appreciated as his essay on the Iliad.

In the Fergusson College Savarkar and his group of young patriots had adopted the practice of dressing in similar clothes and completely boycotting anything that was foreign. Savarkar by now was also an ardent believer and follower of Lokmanya Tilak. A revering follower.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor of Modern History at Kurukshetra University and a member of ICHR)

Comments