How Pakistan deals with Jadhav’s case after the ICJ verdict will be a litmus test for Islamabad’s commitment to seeking normalisation of ties with New Delhi

Pakistan is under pressure and it is showing. Just this week it agreed to many of the Indian demands pertaining to the Kartarpur corridor negotiations including the construction of a bridge on the zero line of the Kartarpur corridor, allowing 5,000 pilgrims each day, and visa-free travel for Indian passport holders. And then days after suggesting that it would not open its airspace for Indian use until India withdraws its fighter jets from forward positions, Pakistan, in a dramatic shift, decided to allow Indian planes use its airspace. This was followed by Pakistan’s Punjab province registered FIRs against Hafiz Saeed and his accomplices in 23 cases related to terror financing and money laundering. Clearly, this is an acknowledgement that Pakistan is hurting because of its global isolation and it needs to take actions in order to enter the ‘civilised’ world.

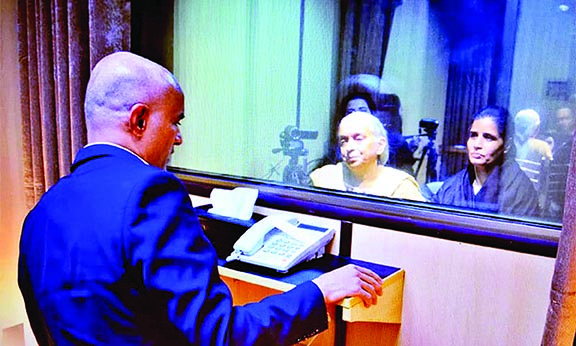

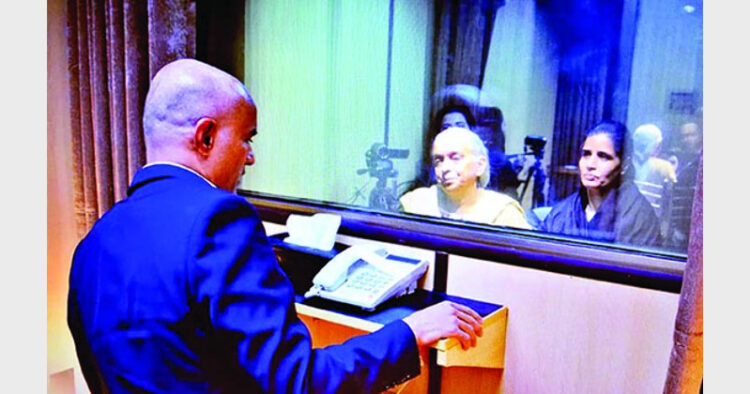

Kulbhushan Jadhav meeting his family members in Pakistan

But then came the ruling of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at the Hague in favour of India that former Indian naval officer Kulbhushan Jadhav’s trial under espionage and terror charges in Pakistan violated international law. It exposed how the domestic dysfunctionalities of Pakistan continue to hinder its normalisation and how disregard to basic legal norms makes it a global outlier. The ICJ, which comprised of 16 members, of whom only one dissenting voice belonged to ad-hoc judge, Tassaduq Hussain Jillani, a former chief justice of Pakistan, decisively ruled against the death sentence awarded to Kulbhushan Jadhav by a Pakistani military court, staying his execution and asking Pakistan not only to grant Jadhav consular access, a right he had been denied so far in violation of the 1963 Vienna Convention but also to review the death sentence ordered by a military court at a closed trial.

Pakistan can make a strategic break with the past or it can repeat its past of making tactical adjustments to pressure from outside only to revert back to its dysfunctional foreign policy. Either way, the ball is in Rawalpindi’s court While the decisions of the ICJ are technically non-binding as the world body has no mechanism for enforcement but it is the world opinion that is behind such judgements. New Delhi’s decision to take the matter to the ICJ was ridiculed by many at home but the strategy was quite clear and the verdict has underscored Indian view by managing to put the spotlight on Pakistan’s frayed domestic institutional fabric where even laws to which it is a party are not adhered to. And by reinforcing Pakistan’s ‘rogue’ credentials, it squarely puts Pakistan and its leadership in the dock.

Of course, Pakistan has tried to put on a brave face. Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan has tweeted that he appreciated the world court’s decision “not to acquit, release and return Jadhav to India” as Jadhav was guilty of crimes against the people of Pakistan and the country would proceed further as per law. But the impact of the ICJ verdict would not be lost on a nation already reeling from multiple crises. Reports have emerged that Islamabad would be exploring third-country diplomatic assistance to manage the Jadhav affair and can potentially do a deal with New Delhi whereby Jadhav is sent home in return for an official admission from India that he was engaged in espionage. This is a trope it had tried to use even in 2017 to no effect as India saw through Pak’s game plan and it is unlikely to work even now.

The ICJ decision also comes at a time when Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan heads to the US for his first meeting with President Donald Trump, seeking a boost to his flagging leadership in the country and as a precursor to ending Islamabad’s wider global isolation. India’s multi-pronged strategy of using various instrumentalities of power – legal, diplomatic, economic and military – seems to be having some effect in shaping Pakistan’s behaviour. The Modi government, in its first term, had faced a lot of criticism for having no policy on Pakistan. To those critics, it should be clear now that not only was there as sustained policy but it was part of a broader foreign policy approach which seeks to make India a leading global player and break the mould of being seen primarily as South Asian player forever boxed in by Pakistani shenanigans on Kashmir and terrorism. It was Modi’s initial outreach to Pakistan in his first term that made Balakot air strikes possible.

From accepting most of the Indian demands on the Kartarpur corridor negotiations earlier this week to opening up its airspace and arresting Hafiz Saeed, Pakistan is now signalling that it is keen to reopen the dialogue process with India. New Delhi can be excused for being skeptical and taking its time in responding to this outreach. How Pakistan deals with Jadhav’s case after the ICJ verdict will be an important test case for Islamabad’s commitment to seeking normalisation of ties with New Delhi. Pakistan can make a strategic break with the past or it can repeat its past of making tactical adjustments to pressure from outside only to revert back to its dysfunctional foreign policy. Either way, the ball is in Rawalpindi’s court.

(The writer is Head of the Strategic Studies Programme at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi)

Comments