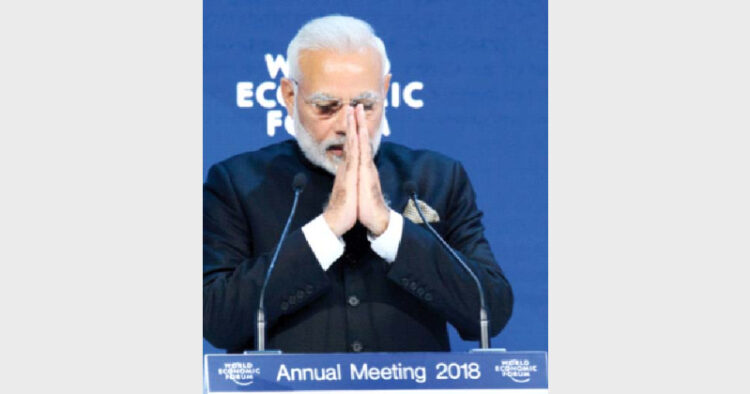

Projecting India as a favourable investment destination, Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed the opening session of the World Economic Forum 2018, becoming the first Indian Prime Minister in two decades to join the world’s top business leaders in the Swiss resort town of Davos

Projecting India as a favourable investment destination, Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed the opening session of the World Economic Forum 2018, becoming the first Indian Prime Minister in two decades to join the world’s top business leaders in the Swiss resort town of Davos

Kanwal Sibal

Prime Minister Modi’s address at Davos deserves to be acclaimed. His oratorical skills are well-known, of course, but even by his high standards he delivered a masterful speech. He was in full command of the subject, touched upon the key themes on the international agenda from the Indian perspective. But what he said went beyond India’s parochial concerns; he spoke as a world statesman surveying the global scene and registering the shared concerns of all those who are conscious of the lenges that an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world is presenting to the collective interest of the

international community.

Of course, PM Modi did not go to Davos to merely deliver an assessment of the state of the world. The principal reason for his trip there was to deliver a message to the world’s top CEOs and other economic players present about the growing opportunities for business and

investment in India that his

government is generating through

various reforms and business friendly policies. Modi is particularly adept at this because he goes into the details of policy making and masters facts and figures as very few leaders do. This makes his pitch to the would-be investors much more persuasive. Modi has clarity of vision and knows where he wants to take his country to, which is why he is an exceptionally powerful messenger for India abroad.

PM Modi highlighted three issues of concern in particular. The growing

sentiment against globalisation in the West, which is of particular concern to developing countries. Even though

economic globalisation has generated inequalities within and between nations, it has significantly contributed to growth and development in the developing world. The biggest beneficiary of

globalisation has been China, for instance. For India the growing negative sentiment against globalisation is

building up at a time when India is

creating more congenial conditions at home for foreign investment and has launched ambitious programmes of national rejuvenation to which foreign funds, technology and expertise can contribute. Modi rightly emphasised that countries have to solve problems together and that a fractured world would not be able to do so. He

cautioned against protectionism and raising of barriers between countries. Rather than being inward looking, countries should follow flexible policies in times of need, he stressed.

On terrorism, he repeated what had been said before by many in several forums but not practised, that is

distinction between good and bad terrorists must not be made. In reality, such a distinction has long been made in our direct neighbourhood, at our cost. On Climate Change, until Shri Modi reversed that perception, India was long considered obstructive in international negotiations on the subject. Today, India has taken a leadership position on the issue, especially by launching the International Solar Alliance along with France and promoting ambitious plans for green energy at home.

Modi’s foreign policy approach is to make India a constructive partner in addressing the issues before the international community. He wants India to be seen as a bridge builder between countries. This would be the most practical way for India to gather support for its national goals from partners abroad and evolve into a leading power. India’s rise is being seen as benign, unlike that of China. While India seeks its due place in the international order, whether in the UN Security Council or the international financial institutions, it does not seek to subvert it. It is the fundamental difference in political systems, in the concept of human freedoms and human rights, in values in general that can generate a rejection of the existing world order and an effort to replace it if possible or modify it

substantially. India as a democracy that shares many values with the West and conveys a sense of comfort to the latter that despite the existence of differences between it and the developed world on many issues, India is not in the business of a self-centred quest for power at the expense of others.

India’s growth ambitions do not threaten the rules based international order unlike as China’s ambitions are increasingly seen as doing. No wonder the US is now criticising China for its predatory economics and, as reflected in the just released review of US defence strategy, China is being viewed as a strategic

competitor. This implies that the US will henceforth see China less as a partner and more as a rival. In

international conferences today concern is widely expressed about the impact of China’s rise on a rules based international order. To be fair, such concern is also expressed about the US under Trump in view of the latter’s “America First” slogan and disinterest in making the spread of democracy and US values a key feature of US foreign policy. Concerns about the China factor make India a valued partner for establishing a strategic balance in Asia, for which strengthening India becomes an objective goal. Modi spoke out in favour of globalisation, as did President Xi at Davos last year, with the difference that China sees globalisation as a means to continue liberally accessing the West’s market, know-how and technology, continue building China’s own strength through this and then use the muscle developed to challenge the West, whereas India sees globalisation not as a tool of self-aggrandisement but as a means to build collective prosperity. Hence, Modi’s message at Davos about India’s philosophical commitment to the concept of “All the world is a family” and his invitation to the audience that if they want wealth with wellness, health with wholeness and prosperity with peace, they should come to India.

(The writer is former Foreign Secretary to the Government of India)

Comments