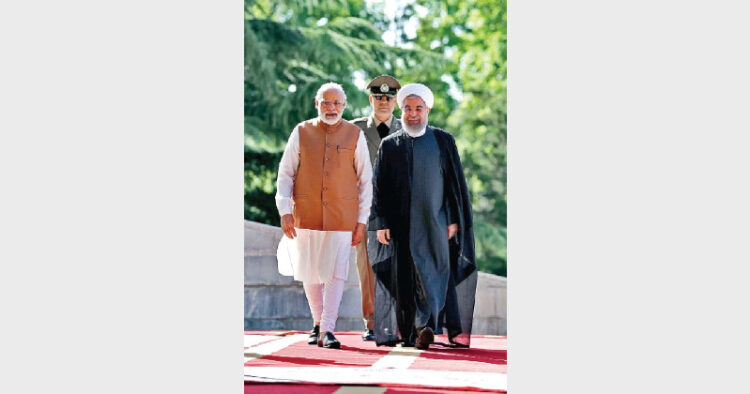

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Iran is said to be his most strategic tour till date. The impact of this tour will be felt in coming years as India begins to increase its economic and strategic footprints in Central and the West Asia

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Iran is said to be his most strategic tour till date. The impact of this tour will be felt in coming years as India begins to increase its economic and strategic footprints in Central and the West Asia

Shebonti Ray Dadwal

Energy has been one of the priorities in India’s relations with Iran. Yet during Prime Minister Modi’s visit to Tehran – the first by an Indian Prime Minister in 15 years – energy was not among the 12 agreements signed by the two sides. Instead, overshadowing the numerous bilateral agreements signed, ranging from science and technology, railways and transport, culture, metals (aluminium) and education, the agreement on the joint development of the Chabahar port, wherein India committed to provide a $500 million credit line plus several thousand crores of rupees for the implementation of development of the port and related infrastructure, including railway lines, was always meant to be the centrepiece.

|

Highlights of Bilateral Agreements

|

However, it would be incorrect to say that the PM’s visit did not include an energy component. A month before the Prime Ministerial visit, Petroleum Minister Dharmendra Pradhan visited Iran in April to discus many topics including increasing the quantum of Iranian oil exports, potential gas/LNG supply projects and India’s investment in the Farzad B gas field, which may be finalised later in the year. Although no concrete deals were signed during the visit, Dharmendra Pradhan told his Iranian counterpart that Indian companies were ready to invest up to $20 billion in the country’s energy sector, both upstream and downstream, and discussed the settlement of pending dues for oil imports. As he stated, the “energy sector can be determining factor in development of Tehran-New Delhi relations.”

Moreover, as part of the Chabahar deal, India plans to set up numerous factories that would run on Iranian energy resources, thereby allowing India access to Iranian energy—but in a manner that demonstrated India’s commitment to forming a partnership that would be mutually beneficial. As Prime Minister Modi stated in his message, India is ready to commit to a long-term and broad-based strategic partnership with Iran that would go beyond mere trade.

India in West AsiaRanjit Gupta Prime Minister Narendra Modi has exhibited a unique ability to establish particularly close personal relationships with the Heads of State/Government of countries that he has visited or otherwise met. He has invested more energy and time personally on deepening India’s relations with foreign countries than any Prime Minister. |

No doubt, looming large in the background to the visit is also Iran’s growing ties with China, and to that extent, Modi’s visit is as much strategic as it is about economics. As the Iranian President Hassan Rouhani succinctly stated, the agreement “was not just an economic document but a political and regional one”.

In that respect, the Chabahar project has the potential to realise India’s plan to strengthen India’s reach in its near abroad, an issue that successive Indian governments have been talking about but delivering little. For years, India has been looking for a direct access to Afghanistan and Central Asia, which it was denied by Pakistan’s refusal to allow transit rights. India signed an MoU with Iran on developing Chabahar, located in the south of Sistan and Baluchistan Province in Iran with access to both the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf way back in the 1990s. In 2003, Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee had once again announced his government’s decision to build the port, but the sanctions regime that was imposed on Iran saw little, if any, movement on the development of the project, although it did use the port to transport wheat to Afghanistan in 2012. Now, with the sanctions regime imposed on Iran withdrawn, India has the opportunity to resuscitate its interest in the project. The fact that in the interim, China’s investment in Gwadar port in Pakistan, which provides Beijing with a trade route for its western Xinjiang province to the Arabian Sea, with potential security risks for India – as well as shipping routes from West Asia in general – may have galvanised India into action cannot be ignored. Wary of India’s strengthening ties with the US, Pakistan is crucial for Beijing’s strategy vis-à-vis South Asia to balance New Delhi’s growing regional and international clout. Gwadar is hence a lynchpin of China’s $46 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – which in turn is a key component of China’s grandiose One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative – and envisages creating a link between Kashgar in China through the length of Pakistan, including parts of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir areas of Gilgit and Baltistan, and terminating in Gwadar port. Couched in development jargon, CPEC represents a part of China’s effort to deliver security through economic development in its restive Xinjiang province as well as providing another facet of its attempt to alleviate its Malacca dilemma. But more importantly, given Gwadar’s potential to serve as a naval base for China’s expanded blue water fleet and operations throughout the Indian Ocean, does give rise to concerns for India.

It is in that respect that Chabahar is crucial for India, both for its energy security as well as its larger security concerns. Not only does it provide access to Afghanistan and Central Asia, but it also provides it the opportunity to play a larger role in its extended neighbourhood and beyond. Through Iran, India can access the International North South Trade Corridor (INSTC) to Europe, allowing it to circumvent and shorten its current and more expensive sea route through the Red Sea, Suez Canal and the Mediterranean.

Nevertheless, there are challenges ahead which need to be dealt with deftly if India’s Iran strategy is to succeed. First, dealing with Washington. Soon after the deal was signed, several US senators questioned whether India”s development of Chabahar violated international sanctions. Although the State Department has supported the deal, they have made it clear that it would be monitoring the project very closely as despite the lifting of sanctions, some restrictions in trade between Iran and other countries continue to be in place. It remains to be seen whether the US will try to place impediments to India’s growing engagement with Iran and whether India will be able to fend off such attempts, if any, without jeopardising relations with Washington.

Second, China’s presence in Chabahar cannot be ruled out. Following Chinese premier Xi Xinping’s visit to Iran in January this year, when a joint statement was made on development of ports as an area of cooperation, a Chinese delegation also visited the Chabahar free trade zone in April and expressed its interest in developing the port and constructing an industrial town there.

Third, Iran’s propensity to play China against India also needs to be monitored closely. Not only is the Iran-China bilateral trade several times larger than India-Iran trade, Beijing has also invested hugely in Iran. Moreover, Tehran has also welcomed China”s Maritime Silk Road initiative.

At the same time, Iran too cannot afford to ignore India, be it in terms of its growing international stature as well as economic clout. India is and will continue to be a market that will be coveted by energy exporters, and Iran will have to match steps with several rival contenders.

Finally, last, but not least, one of the biggest challenges will be India itself. Given India’s past record with regard to project delays, India will have to ensure speedy implementation of its agreement commitments. Having succeeded in signing a strategically important deal that has the potential to change the rules of the regional chessboard, it is in New Delhi’s interest to see that it does not allow it to flounder at the hands of its own domestic constraints or external spoilers.

(The writer is Senior Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies, New Delhi)

Comments