An intriguing study of Sardar Patel’s leadership which addresses a key counter-factual question about Patel being the first PM of independent India

British Marxist historian EH Carr termed counter-factual history as ‘parlour game of losers’. To put it simply, counter-factual history means asking ‘what if?’ in this narrative of historical events. Had something occurred differently, what would have happened then, and how present would have been a different present!

Puranik, Rajnikant, Sardar Patel- The Best PM India never had, Pustak Mahal (Delhi), Kindle Edition, 2018, p. 297

Rajnikant Puranik poses a counter-factual proposition. ‘What if’ Sardar Patel would have become India’s first Prime Minister. He goes a step further to argue that Patel was in fact, the best PM Indian never had. To put some flesh on the bone of this argument requires a close examination of Patel’s life, ideas, adventures, and comparison with his other equally significant compatriot Jawaharlal Nehru. The author does all the same and brings out a book which is compelling, challenging and fun to read. The book under review is an abridged version of the author’s other book, titled, Sardar Patel: The Iron Man who should have been India’s First PM.

Anatomy of the Text

The entry point in the Puranik’s monograph is the integration of the Princely States. He outrightly states that, ‘It is not fully appreciated, but if one studies the unfolding pre-independence and the post-independence scenario between 1945 and 1950… one has to acknowledge that it was not Gandhi or Nehru or any other leader but Sardar Patel who displayed an indispensably wise, critical, mature, decisive, responsible, steering leadership role.’ Therefore, what the author sets out to write on is not entirely Patel, the man, but Patel, the leadership. It is not a study of noun per se; it is an intriguing study of the adjective!

The book begins with a chronological outline of Patel’s life, takes a sneak peak in his early life, and introduces the reader with the contributions Patel made in the freedom struggle movement during 1917-43.

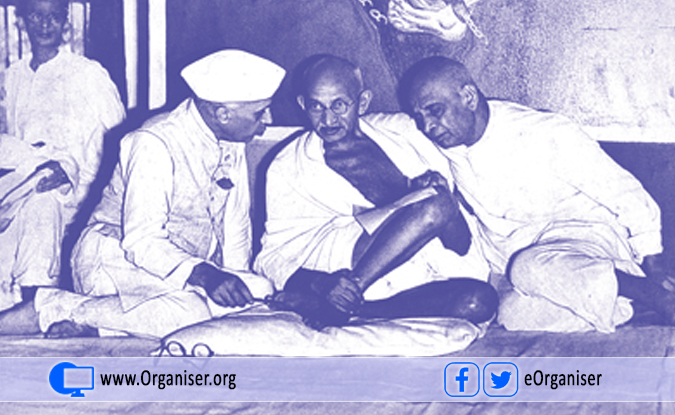

Was Congress unfair to leaders like Sardar Patel with right-of-centre ideology From Left- Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel

In the next chapter ‘Sardar & Run-up to Freedom, 1944-47’, Patel’s role and his diplomatic craft are talked about when the Colonial State commenced the bargaining process regarding the ‘transfer of power’. In the chapter titled ‘How India was deprived of the Best First PM’ Congress Presidential election, 1946 has been discussed at large. What is fascinating is that the author has relied upon a fair share of primary and secondary sources to make his case. Quoting Maulana Azad, Jai Prakash Narayan, Durga Das, Acharya Kriplani, and historians like Stanley Wolpert extensively, the author shows how the path of Patel becoming PM was sabotaged by likes of Nehru in Congress Working Committee.

What the author sets out to write on is not entirely about Patel, the man, but Patel, the leadership. It is not a study of the noun per se; it is an intriguing study of the adjective!After that, Patel’s role and defining contribution in leading to the integration of the Princely States has been discussed. Discussing the brawls between Nehru and Patel on many contentious issues like Kashmir (Reference to UN and Article 370), China and Tibet, Foreign Policy, and Goa, the author has established the historical context for referring to the political thought of both the leaders.

In Indian textbooks on political thought, Nehru is discussed at large, and Patel goes on missing. Puranik fills the gap here! On the issues of Socialism and Secularism, the author has compared and contextualised the thought process of Sardar Patel and Nehru. Remember, for the author, the quest is to choose the better of the two leaders and therefore, his comparison tends to be objective and avoids the unnecessary historical ambiguities.

Lastly, the author delves into Patel as a practitioner by examining the institutions like Civil Services which he helped in shaping up for the post-colonial State. His role in the Constituent Assembly has been analysed, and other more subtle political qualities like how he was non-dynastic and non-nepotistic have been underlined.

A more full-proof concluding chapter titled ‘Injustice to Sardar’ acts as a watchdog for his legacy. It addresses troubling questions as to how Sardar was met with unjust treatment while he was alive, and when he died. Issues like why he was awarded Bharat Ratna in 1991, how Nehru advised Rajendra Prasad not to attend Sardar’s funeral in erstwhile Bombay, and how the publication of his collected works was derailed by those in the Government are discussed. It has also been pointed out that there is no memorial for Sardar in the national capital.

However, as a relief, Puranik also mentions the upcoming Statue of Unity in Gujarat, and how in this way, his legacy is being retrieved in contemporary India under PM Narendra Modi.

The author has made fair use of the rich bibliographical material in the book. Since the canvas of his subject is fairly large, the listings in the bibliography corroborate the same.

The book fails on one account only. In its quest for serious counter-factual exercise, it fails to answer that despite having so many differences between Nehru and Patel, why they went on working together. Had Patel lived more, was a split possible within the Congress? How present India would have been different had Patel became the first PM of the country? And more importantly, what is the legacy of Patel in contemporary Indian politics? Who represents Patel’s ideas, political stance and thoughts in contemporary Indian politics are also least discussed. Overall, a good read!

Comments